The fascination of Paradox

Learning from not understanding

© Ioan Tenner 1990, 2010, 2014, 2019

“The thinker without a paradox is like a lover without feeling”

(Kierkegaard. Philosophical Fragments)

Just as sight recognises darkness by the experience of not seeing,

so imagination recognises the infinite by not understanding it..."

(Proclus Lycius)

"Sits he on ever so high a throne, a man still sits on his bottom"

(Michel de Montaigne)

I was captivated by paradoxes from my childhood*. They looked to me like a mysterious, exotic realm of subtle thought and wit, which I hoped to understand and master one day. Like good humour, paradoxes made me think. It appeared that our mind can create impossible things. I liked them. I also observed that other people disliked them; paradoxes were received with suspicion or derision by many people. Paradox was considered something unbecoming and I wondered why. My interest and my gradual discovery of paradox grew from this opposition.

*

In this paper I will not try to have the last word on what paradoxes are. Leave that to the learned and to the convergent thinkers.

I do not, heaven forbid, try to solve paradoxes.

I will not be criticising what is and what is not a flawless paradox.

I do not even feel bound to consider exclusively “regular”, scholarly recognised, logically orthodox paradoxes.

In the following lines I will rather consider what happens when we meet things that appear paradoxical to us. I will start by proposing with youthful boldness that everything appearing paradoxical is a paradox for us, at least for a while. I will consider what these paradoxical things do to us and what we can do with them.

This paper claims that paradoxes are fertile and useful; they could give us more freedom and openness in the mind.

*

What logical paradoxes are and how they work

Paradoxes are usually considered a concern reserved to philosophers, Philosophers invented paradoxes and then worked hard to solve them and get rid of them. Akin logical “bugs”, like aporias, dilemmas (1) ironies or antinomies (2), were treated in the same way, like logical vermin.

They define paradox as, for an example:

“an argument which seems to justify a self-contradictory conclusion by using valid deductions from acceptable premises.” (3)

“A paradox is an argument that derives or appears to derive an absurd conclusion by rigorous deduction from obviously true premises.” (4)

I would retain from this that a logical paradox creates its own world, impeccable in form, but makes it impossible in meaning. Being self referential, it is waterproof to rational sense (5) and to external evidence.

We can observe that logical-mathematical paradoxes are defined by a few features (contradiction, self reference or circularity, absurd coexistence of truth and false…) appearing in a thought process, usually deduction: the development of an argument from premises to conclusion.

Logicians are concerned by what paradoxes are and what they mean for Reason. Their main effort is to find the fault in them and – as I said - to solve it. This negative attitude is understandable. For the logicians, paradoxes announce danger, pain and paradigm shifts. Disorder and insecurity of truth loom above the reassuring world of Reason.

As W.V.O. Quine explained: “The argument that sustains a paradox may expose the absurdity of a buried premiss or of some preconception previously reckoned as central to physical theory, to mathematics or to the thinking process. Catastrophe may lurk, therefore, in the most innocent-seeming paradox. More than once in history the discovery of paradox has been the occasion for major reconstruction at the foundation of thought.”(6)

*

By valuing paradox I seem to go against a healthy rejecting attitude very respectable in logic and philosophy. A scholar like R. M. Sainsbury presents only three possible treatments of a paradox:

“(a) Accept the conclusion as a last resort... but explain why it seems unacceptable ;

(b) Reject the reasoning as faulty;

(c) Reject one or several premises, explaining why they seemed acceptable.” (dissolve them, see them as ignorance, etc..) (6a)

If nothing else works, consider changing the frame of reference: classes, indexicality, self-reference and so on, just do not give up (I'm kidding).

But I do not believe that paradox exists only in the high spheres of logic and metaphysics. I grasp paradox within my own experience. As an uninhibited pragmatist and “psycho-logician” addicted to experience lived, I need to observe three more less logical but de facto things people use to do:

(d) You misunderstand, deny or refuse to consider the statement altogether;

(e) Live humbly with a few paradoxes unresolved as any true believer does;

(f) Transcend or transgress (with or against method) the frame of reference given, the one that makes the statement or the situation impossible, and even, if needed, you transgress, uncaring of the rules given for proper thinking, like a barbarian cutting the Gordian Knot in Alexander-style.

I also believe that we can do better than remain at solving, banishing, denying or misunderstanding paradoxes.

We can put them to use. As they are.

*

Paradoxes outside the field of logic and mathematics

Academic definitions appear to consider only logical and mathematical paradoxes expressed in propositions made of words, symbols or numbers. But paradoxes are, in Culture and in everyday life, more than propositions. They appear in situations, perceptions, feelings, actions, images, symbols and so on. Many domains other than logic encounter paradoxes.

General dictionaries, concerned with what the words usually refer to or in what way they are normally used, are inclined to give more practical and wider definitions to the term paradox (my highlighting):

“1.a. A statement or tenet contrary to received opinion or belief; often with the implication that it is marvellous or incredible; sometimes with unfavourable connotation, as being discordant with what is held to be established truth, and hence absurd or fantastic; sometimes with favourable connotation, as a correction of vulgar error...

2.a. A statement or proposition which on the face of it seems self-contradictory, absurd, or at variance with common sense, though, on investigation or when explained, it may prove to be well founded (or, according to some, though it is essentially true).” (after Oxford English Dictionary, 2009)

“Paradox [Gk paradoxon], contrary to expectation.

1: a tenet contrary to received opinion

2 a: a statement that is seemingly contradictory or opposed to common sense and yet is perhaps true

b: a self-contradictory statement that at first seems true

c: an argument that apparently derives self-contradictory conclusions by valid deduction from acceptable premises

3: something or someone with seemingly contradictory qualities or phases.” (Merriam-Webster, 1994)

I observe that the defining features are, in this wider sense, features that strike us when we meet paradoxes: unexpectedness, differing from common opinion on the subject matter, surprising method or conclusion, being unbelievable, amazement, absurdity, consternation, contradiction but also…the potential to express the complexity of truth (7) and wisdom, as they appear to us in "real life".

As a consequence, the public concern could be more discerning than just finding the errors and reducing paradoxes to accepted knowledge.

It may in fact be interesting, instead of finding error, to examine all shocking newness on merit. In the sixteenth century many people spoke of the Earth’s motion as the paradox of Copernicus and Galileo (8). Quite often, in common place terms, one man’s clear idea is another man’s paradox (especially when the one man’s idea is new).

A moral philosopher like S. G. Stent, finds that paradoxes are generated by our rational faculty in domains where rationality tests its limits and deep truth is sought; free will vs. determinism, soul, moral responsibility...(9) I find this idea of testing the limits intriguing and fascinating too.

It may be worth, besides the hunting for precision, which is too often a surrogate of truth (10) and for certainty, which is not of this world, to uncover, disguised in paradoxes (11), some hidden occasion to learn and to be wiser. I believe that wisdom – which is for me the person-centred, good sense, shared understanding of knowledge and experience – must often be expressed in the form of paradox. Its complexity requires the gamble of contradiction and the prudent discerning of obscure formulation.

The impression they give, of surprise and absurdity, makes paradoxes (or appearing to be paradoxical) a familiar ingredient of ridicule and of jokes – the pun that provokes laughing. In this wider cultural meaning, paradox is then a recipient or a vehicle of esprit de finesse and of humour.

If it looks like one and works like one...it is one

Let me go further and shift the discussion from paradox to paradoxical.

An openly subjective view of paradox, a working definition as my “everything experienced as a paradox” takes the discussion out of pure theory, into the practical province of thought, experience and action in everyday life.

When you come to “living persons”, anything could "be" paradoxical, that is received as a paradox, if it appears as strikingly new, contrary to established opinion or belief, self contradictory, serioussly unexpected or compelling in what it shows or implies, but is impossible to understand.

Such a light and situational view of paradox is less concerned with what paradoxes must be but rather with “how they behave” and what they do to people.

Psychologists found real life abundant of “double binds”, cognitive dissonance, moral dilemmas and so many other blocks, states or situations that look to me very much like paradoxes with or without words.

For authors like - in my youth - Paul Watzlawick, paradoxes, as bugs in the mind, are frequently the very form in which difficult problems are created and in which locked solutions induce and perpetuate a crisis they are meant to prevent or resolve. Many self perpetuating problems can be identified in such dysfunctional blind spots.

Parents, teachers, lovers and leaders give sometimes paradoxical instructions, make conflicting demands that paralyse and beat the mind when the victim is unaware and unable to discard them:

“Be spontaneous!”

“Do not read this sign!”

“Be natural!”

“Be yourself!”

“Be independent!”

“Go to your room and don’t come out until you have a smile on your face!”

“Don’t take notice of my presence!”

“You should trust me!”

“Why don’t you want to love me?”

“I want you to like me of your own free will!”

“Discipline must be freely accepted!”

“You must change the way you think!”

“You must stop believing this!”

“Don’t think evil!”

“Please ignore my previous mail”.

Orders of this kind are impossible to obey from the very moment they are uttered. They are seemingly meaningful but contradictory and absurd. Their impact is destructive or at least destabilising. They may create “double binds” as described by Gregory Bateson in the ‘1950s. Such tension unresolved is a provocation to madness or at least, to duplicity and double-talk. These “games of not playing a game” create the problem they pretend to prevent. The skill to detect such paradoxical circumstances allows one not to solve them, but to detach from their grip, cope with them or to evade them by rebellion.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma proposed by game theory generates situations of paradox – trust versus irresistible rational distrust (see William Pounstone, Prisoner's Dilemma, Oxford UP, N.Y...,1992). Common sense distrust leads the “prisoners” to act in a vicious circle, in the name of compelling prudence, finally against their best interest and to their inexorable loss. On reflection many situations where mutual exchange is based on trust turn to paradox: applying the millennia-old Golden Rule or Kant's imperative to only do what could be turned into a rule applied by all, generate situations of paradox. Likewise, the necessity to surrender some freedom to others and to submit to laws in order to stay free is, at core, paradoxical.

The study and the diagnosis of paradox proved also to be a gold mine of original, often paradoxical solutions to blocked situations and impossible problems. Psychologists found that prescribing paradox – making a situation as absurd as possible - can lead to the solution of seemingly insoluble situations.

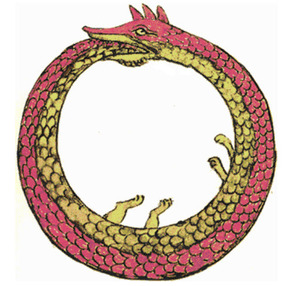

Another field rich in paradoxes is art. Artists like Maurice Escher or Salvador Dali demonstrated to our eyes impossible perceptions “that can’t be, but still are”.

Image paradoxes typically called optical illusions are coercing the spectator (or the victim) to perceive things that can’t be, according to common sense; Impossible triangles, water flowing down - upwards, hands drawing each other. These are paradoxes formulated not in words but as objects and perceptions grew to be part of the universal visual vocabulary of humanity.

This is not only amazing and beautiful. It is challenging; I also found those images eye-opening. I used such optical and other illusions to help people learn with their own eyes that seeing is not always believing. There are few such ostensive means to persuade one to become more critical with the obvious.

Literature is another source of paradoxes (12). Writers like Franz Kafka and George Orwell exposed entire totalitarian dystopias were words mean their contrary and where people are damned if they do and also damned if they don’t. Jonathan Swift, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells with his time machine, Oscar Wilde ("Those who try to lead the people can only do so by following the mob”), Lewis Carroll, Joseph Heller (Catch 22) are a few examples of literature rich in highly meaningful paradox.

Private and corporate lives are crawling with the absurdity of political correctness, double-talk, perverse effects, vicious circles and structural contradictions. Aren’t all these paradoxical? Paradoxes that appear as dissonant structures of people and contradictory, self-defeating relationships?

Situational and organisational paradoxes are less studied scientifically, at least by the end of the twentieth century (or I do not know enough about that study). An investigation of organisational paradoxes identified eleven of them: stability vs. change, empowerment vs. control, people focus vs. organisation focus, consistency vs. flexibility, internal vs. external, narrow vs. large picture, means vs. ends, soft vs. hard, individual vs. group, words vs. actions and trust vs. mistrust (13). Some of them may be structural or they stem from the self-fulfilling prophecy or compelling paradigm of a founding father. Such paradox will re-create itself for a long time before being exposed as utopia or dystopia. Others are, I think, “ways to hell paved by good intentions”, group-think and perverse effects of cultural bias and politically correct hypocrisy in big organisations.

A whole political system can become a paradoxical one in which, as my mother - a historian - used to jest, even “the past is most difficult to foresee” because it will be continually falsified to fit current dogma. Under totalitarian tyranny – right or left - contradiction is carefully cultivated between thought, speech and action. In such worlds good is bad, truth is lie, freedom is submission, ugly is beautiful, soldiers fight against war and everybody is born a sinner and a suspect, doomed to prove his innocence forever. Orwell and Kafka and Soljenitzin describe such tyrannies at their extreme.

Religions like Taoism and Zen Buddhism appear to use paradoxical Koans in order to produce major liberating change by crisis in people’s mind. The stress of trying to find the meaning of paradoxical statements, differentiating things from themselves or of achieving spontaneously prescribed states of mind destabilises, it seems, to the point of producing quantum leaps of faith or of comprehension. Many sects seem to use such devices to lure people into leaps of faith in the opposite direction of dependency.

*

While reading this enumeration, you may believe that I write here to deplore paradox for its negative instances of manipulation and suffering. However, as I announced, my goal is different. I stress how the ubiquitous paradoxes feel and “behave” because I seek to learn something useful from what they do to people.

What good things could we do with such painful paradoxes?

Let me affirm the enlarged field once more. For me, as a psychologist, if people experience something as a paradox, then, for them, it is one. The impact will be that of a paradox. I mean to say that being paradoxical will suffice for any item to institute a “paradox” locally. You can paradox most of the people some of the time… and that is enough.

Observing this feeling of paradox I appreciate the value of such things, narratives and situations that act upon people’s minds, surprise, challenge or numb them and leave them as perplexed as the electric-eel of Socrates is reputed to have done. I look at this traditionally disquieting field with the eyes of the teacher and of the giver of counsel.

The following will then be my working definition:

For this paper paradoxical is something (a statement but also a thought, a feeling, an object, an image, a question, an instruction, a choice, dilemma, a situation) that leads into or keeps our perception, our reason, our feelings or our action in an impasse and which invites surpassing, some radical change of mind.

The premises or perceptions leading to an experience of paradox are obvious, acceptable, plausible and compelling. My eyes or ears, my fingers, my experience, should not cheat me, and the reasoning or the perceived transformations appear to be sound and self-evident to my common sense and my intuition. They may even be necessary to logical thought (as logical paradoxes show to be). However, the meaning implied or the conclusion reached appear impossible and with no way out.

It had better be a joke. The feeling of paradox is most often irritating, even threatening. What befalls me goes against my common sense, against the stability and coherence of my world. It undermines my certainty, my faith. Some simple, basic, unquestionable values and deep beliefs, about truth and reason, my very intellectual makeup may be threatened if I take this seriously. If God Almighty cannot (or can) create a stone too huge for him to lift is He almighty? I feel tired to think further. I better laugh it away and say that it is stupid. Or stone the author and burn his book. Or quit. I am so busy with other business.

Living a paradox leads us through mental dissonance; it may also open us to new, reformed understanding.

In time, my own encounters with paradoxes taught me something I call fascinating: The “paradoxical” gut feeling of experiencing something “impossible” is a unique symptom. A symptom of touching one of two limits of my mind:

(1) its’ outer frontier – what I don’t know (and did not know that I don’t know), or

(2) its’ inner foundation – the obvious, the basic unquestioned “axioms” that guide my reason, my values and my daily life.

I mean that the feeling of paradox is a “detector of the Unknown” or an “exposure of unexamined certainties”. As Proclus wrote "Just as sight recognises darkness by the experience of not seeing, so imagination recognises the infinite by not understanding it..."

When I write about the outer frontier of the unknown I have in mind one of its major problems; that we usually don’t know what we really don’t know; and not only by definition. Of all people, those who need most to grow and change to the better, are unaware, even totally unaware, often in denial of their ignorance. How to find out the direction in which we need to seek? By what means to become aware (as Socrates made us) that we are ignorant where we believed we knew?

Dramatising and making intuitive about what, or in what direction we are ignorant, is in my opinion precious for both the masterly teacher and the deserving learner.

The same applies to the other end, so to say, of our usual lack of critical thinking concerning the obvious. I even believe that the unexamined obvious is a worse enemy of learning and changing than unsuspecting ignorance. Received beliefs or past successes become part of our persons and certainly of our culture. People are made of their preconceived knowledge to such an extent that they feel deeply threatened when their basic beliefs are questioned or put to test.

The paradoxical way of compelling one to reconsider the “obvious” is one of the rare means to access the strongholds of the mind.

If what I claim is true it means that we have here a tool to detect that which we do not know or cannot conceive or never considered critically. Allow me the metaphor: I call it a philosopher’s stone of critical thinking (14).

*

Let me pause and take leisure by recollecting some old examples of paradoxes:

The strongest paradox known in history is probably the one “of the liar” that of Epimenides the Cretan who claims that all Cretans are liars: a correct statement that ends up in havoc: I read:

“This statement is false.” A medieval formulation of it is this imaginary argument between Socrates and Plato:

Socrates: Everything Plato will say here is false.

Plato: Socrates spoke the very truth.

If this is true, it is false. If it is false, it is true. This is not normal. This is not what I learned in school. The disciplined mind needs to solve this. For my undisciplined mind this is a provocation to ask what truth is.

Many grains of sand form a heap. If you take away one grain, it is still a heap. You keep taking grains away. When is the heap no more a heap?

I do not care to solve the vagueness problem, but it makes me think of soft water drops that pierce hard rocks. It reminds me that it is the last straw that breaks the camel’s back. The accumulation of small nothings may bring big change.

I will ask you to answer with “yes” or “no” only, the following question: “Will your first answer to this question be “no”?”. If you say “yes”, you lie. The same if you say “no”.

If you give a thought to this impasse, it is one little example of how language is relative and limited; there must, of course, be something like language about language. There may also be times when we should free ourselves from words.

An example of paradoxical ruse:

Euathlus the apprentice lawyer had a contract with his teacher Protagoras the Sophist master; he would only pay a fee for the teaching if he won his first case in court. Euathlus had a clever idea. He sued the master himself to obtain free tuition. If he would lose this first case, he had nothing to pay, as agreed. If he would win, he will not pay, by force of law.

Just imagine the endless ruses this “turning a thing on itself” can inspire. And imagine the power of being able to change the frame, the context by which meaning is given.

The Zen teacher formulates koans, questions impossible to answer:

“What happens to my fist when I open my hand?”

“What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

“If a straight line is an infinite circle, then where is its centre?”

“Kuang Tze dreamed one night, he was a wonderful butterfly, enjoying the breeze in the sunny field. Then, he woke up and he didn’t know any more: was he Kuang Tze heaving dreamed being a butterfly, or was he a butterfly dreaming now that he is Kuang Tze?” (Chuang Tzu, The Inner Chapters)

The growth solution of a koan is (in my opinion) to gain autonomy from the question itself. It is formulated with the intention to exasperate the learner to such an extent that he would in the end break the “catch” in a sudden illumination that all the rules can be disobeyed and transgressed in the mind. This is, in intellectual terms, a satori. Perhaps...

Religious ethic has its paradoxes too:

If God is good, all-mighty, and all-knowing, then how can

there be so much suffering and evil in the world?

The result was scepticism and loss of faith for some or endless theodicy to justify God’s ways for others. For me this mainly demonstrates what happens when abstract ethic meets complexity and life. It tells me that ethic choice is our mind size struggle with disorder in the name of being as good as we can. It means that there is as much goodness in the world as we put into it.

My favourite creation of a mild feeling of paradox by utmost banality is to tease you:

“I will here and now create, because I please so, a piece of truth that I challenge you to refute if you can. Here it is: ‘There are only two kinds of people: Those who believe that there are only two kinds of people, and those who don’t‘”

Let me stress this: we can create a feeling of paradox. We can generate and wield the magic wand of paradoxical experiences, to make people’s minds open and move.

*

The question that inspired this paper is: “Why is Paradox so fascinating?” It is time to justify my answer: “Paradox is fascinating for me because it makes reason bend beyond itself. I understood as I kept teaching and growing older that, in everyday life, paradox is not only a mere “bug in the mind” but also a Master tool. I will try to explain this by example, through my own way of rediscovering the ages old tool and of using it.

Paradox is fascinating as an instance of learning from not understanding.

Carefully administered, the puzzlement induced by paradoxes enables me and the people I work with, to detect things beyond the field of what we already conceive: “Just as sight recognises darkness by the experience of not seeing, so imagination recognises the infinite by not understanding it.” (Proclus Lycius, 412-485 AD, A Commentary on the First Book of Euclid's Elements).

I realise that this is quite a strong statement, laden with metaphor. I do not intend to appear mystical. The fact is that this observation seems to work. I believe that understanding and using paradoxes allows a practical approach to our inner limitations, structural or caused by ready-judged ideas, stubborn received beliefs about undecidable issues, unshakeable values and other convictions, too deep or too obvious to be a likely subject of critical discussion. I will take an example from my experience (15) :

How I teach by confusing people

One of my favourite classroom koans in a course of wisdom (which I disguised for many years as a “Management” course) was to lure the participants into an exercise of inventing “things impossible to imagine”. It was an exercise of creativity (16) which I dubbed “a can opener for the mind”.

First I would ask several groups to compete in inventing as many possible things one can do with “bricks”.

This is a very well known and slightly worn-out classic of brainstorming and the participants used to have – as I intend – an appeasing feeling of déjà vu. Easy! Soon, most people understand the playful rule of the game - that we are free and legitimate in the mind to invent whatever we like, provided there are no constraints of rule, law or material limits. They discover that they can even redefine “bricks” to mean whatever they fancy.

After this first teaser, when people were pleased with themselves, I unexpectedly declared that “all this was no real creativity since we only imagined things possible to do with “bricks””. “What about some real creation,” I propose, “like inventing the same amount, but of things impossible to do with “bricks”?”

Now this is a paradoxical injunction and people fall into it, regularly. They are stunned.

First, my students rushed mindlessly into listing a large number of “impossible” things thus contradicting themselves; once they imagined them, how could those things be impossible to imagine? I had to point out that minutes ago they accepted that “everything” was possible in the mind and they just took advantage of this freedom rule.

Now, after some work of challenge, people grew to accept that only very, very few things can be retained as impossible in this occasion. For an example, stating that a thing is not what it is may be retained. Perhaps. This was voted by a majority’s common sense as “really impossible”. The exercise did not end with this.

Now I would ask, again surprisingly: “If it proves almost impossible to find things impossible to imagine, why did we, minutes ago, and why do we imagine so few in our daily life; not do but at least imagine? Where is lost the rest of infinity?” A very formative discussion followed, where engineers, economists, I.T. experts and profit minded managers proved passionate interest for philosophical speculation and meanings of invention.

Reads confusing? All this is very confusing for people who take part in the exercise and I had to appease their feelings, as some felt suddenly lost and inferior. The important thing is that one after the other, at different speeds, people discover by means of this confusion that they have a number of basic assumptions, so obvious to them that they never considered questioning those axioms until this moment. Some feel uneasy but all learn something important. What is it? Participants are left deeply impressed after this exercise.

The unease and the confusion of being paradoxed are privileged ways of coming close to what we do not understand, aware that the obvious can be shallow. A Buddhist saying reminds that “the foot feels the foot, when it feels the ground”.

In the best Socratic tradition, the intuition of being helplessly ignorant in a field where I had no doubt, allows me and pulls me to open and learn new things.

The exasperation of Paradox not only challenges people to grow more open but also gives them a hint where to go and how. It points at a frontier, a rationally conceivable limit of the unknown, of the impossible and of the necessary. The inevitable spirited discussion after my koan is about realms, rules and definitions, about what is possible and impossible. Existence, reality and the limits of the mind suddenly intrigue most un-philosophical people. They sense something we all learned to forget: that in the “meta” realm of the mind, protected with

armour of question marks, quotes, parenthesis and attention marks, one could transgress and reframe almost anything. One could think free. Nothing is impossible to imagination and to thought if there are no rules and no limitations. Error and disorder should not be ruled out from this creation process, as even error could be productive. Of course, error could also result from it. Later, it may be that the outcome of this imagining and trespassing into the unknown and into the impossible need be tested for feasibility to be transferred into real life.

George Bernard Shaw expresses best this enchantment of unfettered thinking in a phrase I am never tired to quote from his “Back to Methuselah”:

“People see things and ask: Why? I dream of things that never where and ask: Why not?”

The use of paradox in education, while investigating the unknown and the non understandable, grows the size of personal freedom. It multiplies choices in the mind. It emancipates people. It helps change. Fascinating, isn’t it?

*

Change is something else

Acquaintanceship with paradox helps here too, by developing the states of mind favourable to coping and surviving unfamiliar change. Let me now look at going through change and governing change.

Things that are truly new appear paradoxical. I believe that this is because they are “out of the system” of our current understanding. In fact, change itself, when it is not of our mind size, is often paradoxical to our perception: if change is too small or too huge, too fast or too slow, too unimportant or too important, too far away or too close to us – we cannot perceive it or cannot respond to it. To navigate change and to create newness

one must be at ease with the unfamiliar and the contradictory instead of becoming defensive or hysterical.

People whose occupation is to bring newness and help change to happen must learn to live with the unknown, the uncontrolled and even with the irrational, untamed for a while (17). They must be able to function even in a state of perplexity. To cope with the never-ending surprise of our fast changing world, familiarity with paradox is a necessary companion. Someone mentally accustomed to live in cohabitation with vagueness, com¬plexity, ambiguity, contradiction suspended, able to survive not understanding, is better prepared to produce something else and to cope with newness.

Learning to live with some things unknown instead of compulsively trying to reduce them to something already controlled is a key to governing change.

I derive from this friendly, non defensive attitude to the unknown, a practice of strategy of surprise in the terms of James Carse who suggests “preparing for surprise”, to complete our customary “preparing against surprise” (18). Preparing for surprise means to become accustomed with the idea that surprises – surges of the unknown - are inevitable; there are ways to respond to them rationally and optimally to overcome the biological enmity to surprise hard-wired in our species.

*

Instead of a conclusion

So, I found paradox fascinating because it is useful as it achieves a rare thing – sensing that which we don’t know.

What to do then, after sensing the unknown? That may be the subject of another essay. One, to examine the means of trespassing into the not yet known. The metaphor of the trespassing is simple: once we detected the unknown territories which we don’t even understand we could at least draw white maps of those unknown continents. Then, we could plan our expeditions to conquer the white map: Normal, study expeditions interrogating other peoples’ knowledge and understanding or bold personal inventions. Maybe even inventions that would make new knowledge arise from nothing. We could create those unknown territories. Isn’t everything possible where are no rules and limitations?

The metaphor is simple. The application may be more complicated...

An old parable illustrates the choice we face once we experienced paradox and find ourselves in presence of the unknown:

When you have little knowledge, it is comparable with the small light of a candle. Its warm flickering creates a small space of friendly, familiar safety.

If your knowledge grows, it is like a street-light. Now you see many more things and you can walk firmly. However, the dark space of night at the confines of luminosity grows too. More things unfamiliar are inevitably glimpsed.

And what happens when you become really learned? Now the space of light is great. But beyond what you know, becomes apparent and even certain huge darkness, the endlessness of things you will never know. You are left alone, small and proportionally insignificant among stars, lost in infinity.

The question is: “What do you chose? Despair in front of the unknown? Rebellion? Urge to deny or to reduce infinity to what you know? Seeking enlightenment from a prophet? Hiding humbly inside a large community of anonymous scientists and begging the future by faith in progress? Or do you accept with modest friendliness to do what you reasonably can and use wisely what you know and knowing more, while coexisting peacefully with the unknown?

*

Let me indulge, after concluding, another touch of self-critical vagueness. My own paper reminds me a story (And I hope that it leaves you with more questions than you had before reading it):

In days of old, in ancient Japan, the summer evenings, bamboo-and-paper lanterns were used, with candles inside. Someone offered such a lantern to a blind man who wanted to go home after a visit.

“I don’t need a lantern. Light or darkness is all the same to me”.

“It is not for you my friend. Without one, someone else may run into you on the road.”

The blind man started off with the lantern and before he had walked very far a passer-by run squarely into him.

“Why don’t you look out where you walk? Can’t you see my lantern?” said the blind man.

“How could I? Your candle has burned out while you walked, my poor man,” answered the stranger.

_________

* Raymond Smullyan, Professor of Mathematical Logic and part-time magician, writes of an incident he experienced when six years old. It was so intriguing that the child would remember it for all of his life:

“It was the first of April 1925. He was sick in bed with grippe. His elder brother, Emile has told him that morning: “Well, Raymond, today is April Fool’s Day and I will fool you as you have never been fooled before!” Raymond waited all day long for this wonderful surprise. Nothing happened. Late that night, his mother asked him: “Raymond, why don’t you go to sleep?” “I am waiting for Emile to fool me.” Mother turned to Emile and asked him to keep promise and fool the child. This dialogue ensued:

" Emile: So, you expected me to fool you, didn’t you?

Raymond: Yes.

Emile: But I didn’t, did I?

Raymond: No.

Emile: But you expected me to, didn’t you?

Raymond: Yes.

Emile: So, I fooled you, didn’t I?

Raymond:? ” *

This is a paradox in the literal tradition of the Greek word (which means etymologically “beyond expectations” or contrary to accepted opinion). It is a variant of the “announced surprise inspection” or “unexpected examination” (of the kind: “this week, you will have an unannounced inspection”). One could find a similar pattern in a note you will read in a bus station, announcing that “The last bus of today will not come”. (Raymond, What is the Name of This Book, 1985)

(1) di.lem.ma 1: an argument presenting two or more equally conclusive alternatives against an opponent 2 a: a usually undesirable or unpleasant choice... b: a situation involving such a choice ... 3 a: a problem involving a difficult choice... b: a difficult or persistent problem... What is distressing or painful about a dilemma is having to make a choice one does not want to make. (c) 1994 Merriam-Webster, Inc.

(2) Antinomy: a contradiction between two apparently equally valid principles or between inferences correctly drawn from such principles 2: a fundamental and apparently irresolvable conflict or contradiction. (c) 1994 Merriam-Webster, Inc.

(3) Nicholas Bunnin and E. P. Tsui-James, The Blackwell Companion to Philosophy,

http://www.blackwellpublishers.co.uk/scripts/webbooke.idc?

ISBN=063118788X

(4) Van McGee in Encyclopedia of Philosophy, Macmillan, Detroit.., 2006, p 514

(5) Some philosophers like B. Russell proposed special conditions to rule them illegitimate, but this is not our concern here. What I find of great practical value in the usage of paradox is Russell's instigation that we must move out and above it to solve it.

(6) "Paradox," Scientific American, 206 (1962) in Suber P., The Paradox of Self-Amendment, Peter Lang Publishing, 1990)

(6a) Sainsbury, R.,M., Paradoxes,(3rd ed.) Cambridge U.P., Cambridge, 2009 passim (ex; p.47, 48, 49, 51, 54, 56 )

(7) Niels Bohr (1949) said that there are two kinds of truth: To the one kind belong statements so simple and clean that the opposite assertion obviously could not be defended. The other kind, the so-called "deep truths" are statements whose opposite also contains deep truth." Bohr, N., (1949). Discussion with Einstein on Epistemological Problems in Atomic Physics. In Albert Einstein: Philosopher-Scientist, Evanston: Library of Living Philosophers, Inc., V.5, p 199

(8) De Morgan, Augustus, A budget of paradoxes, London Longmans, Green, 1872, p.2, 5

(9) Stent, G., S., Paradoxes of Free Will, American Philosophical Society, Philadelphia, 2002

(10) For, precision is not truth, as Henri Matisse said so well.

(11) For an example, a verse from the Tao te-ching like: “The Tao that can be told is not the eternal Tao./The name that can be named is not the eternal name.” is nothing but a paradox for too many people.

(12) Cleanth Brooks concludes an analysis of paradox in literature by claiming that the only way some ideas can be expressed is through paradox.

(13) Horrigan L., M., A paradox Base Approach to the Study and Practice Of Organisational Change, Griffith Univ. 2005

(14) I mean by critical thinking that thinking which examines everything, not only our own thinking.

(15) My favourite and simplest way of using paradox to make the unknown visible in everyday life is to reduce things to the absurd or even better to amplify a subject at hand to the absurd by imagining “total victory”.

(16) In fact it is an exercise for increasing freedom in the mind by means of unfettered thinking - the ability to expand the field and the number of choices we conceive.

(17) I found useful to apply this tool in change management consulting and in adult education. Certainly, far from being my invention, this artifice is ancient. For several thousands of years the Sufi, Tao and Zen ideas were perpetuated in apprentices’ minds by means of amazing allegories and unanswerable questions. I guess that the Greek sophists, Heraclitus, Socrates and the Talmudists did the same.

(18) I proposed a third class of strategy: “preparing the surprise”.

“The thinker without a paradox is like a lover without feeling”

(Kierkegaard. Philosophical Fragments)

Just as sight recognises darkness by the experience of not seeing,

so imagination recognises the infinite by not understanding it..."

(Proclus Lycius)

"Sits he on ever so high a throne, a man still sits on his bottom"

(Michel de Montaigne)

I was captivated by paradoxes from my childhood*. They looked to me like a mysterious, exotic realm of subtle thought and wit, which I hoped to understand and master one day. Like good humour, paradoxes made me think. It appeared that our mind can create impossible things. I liked them. I also observed that other people disliked them; paradoxes were received with suspicion or derision by many people. Paradox was considered something unbecoming and I wondered why. My interest and my gradual discovery of paradox grew from this opposition.

*

In this paper I will not try to have the last word on what paradoxes are. Leave that to the learned and to the convergent thinkers.

I do not, heaven forbid, try to solve paradoxes.

I will not be criticising what is and what is not a flawless paradox.

I do not even feel bound to consider exclusively “regular”, scholarly recognised, logically orthodox paradoxes.

In the following lines I will rather consider what happens when we meet things that appear paradoxical to us. I will start by proposing with youthful boldness that everything appearing paradoxical is a paradox for us, at least for a while. I will consider what these paradoxical things do to us and what we can do with them.

This paper claims that paradoxes are fertile and useful; they could give us more freedom and openness in the mind.

*

What logical paradoxes are and how they work

Paradoxes are usually considered a concern reserved to philosophers, Philosophers invented paradoxes and then worked hard to solve them and get rid of them. Akin logical “bugs”, like aporias, dilemmas (1) ironies or antinomies (2), were treated in the same way, like logical vermin.

They define paradox as, for an example:

“an argument which seems to justify a self-contradictory conclusion by using valid deductions from acceptable premises.” (3)

“A paradox is an argument that derives or appears to derive an absurd conclusion by rigorous deduction from obviously true premises.” (4)

I would retain from this that a logical paradox creates its own world, impeccable in form, but makes it impossible in meaning. Being self referential, it is waterproof to rational sense (5) and to external evidence.

We can observe that logical-mathematical paradoxes are defined by a few features (contradiction, self reference or circularity, absurd coexistence of truth and false…) appearing in a thought process, usually deduction: the development of an argument from premises to conclusion.

Logicians are concerned by what paradoxes are and what they mean for Reason. Their main effort is to find the fault in them and – as I said - to solve it. This negative attitude is understandable. For the logicians, paradoxes announce danger, pain and paradigm shifts. Disorder and insecurity of truth loom above the reassuring world of Reason.

As W.V.O. Quine explained: “The argument that sustains a paradox may expose the absurdity of a buried premiss or of some preconception previously reckoned as central to physical theory, to mathematics or to the thinking process. Catastrophe may lurk, therefore, in the most innocent-seeming paradox. More than once in history the discovery of paradox has been the occasion for major reconstruction at the foundation of thought.”(6)

*

By valuing paradox I seem to go against a healthy rejecting attitude very respectable in logic and philosophy. A scholar like R. M. Sainsbury presents only three possible treatments of a paradox:

“(a) Accept the conclusion as a last resort... but explain why it seems unacceptable ;

(b) Reject the reasoning as faulty;

(c) Reject one or several premises, explaining why they seemed acceptable.” (dissolve them, see them as ignorance, etc..) (6a)

If nothing else works, consider changing the frame of reference: classes, indexicality, self-reference and so on, just do not give up (I'm kidding).

But I do not believe that paradox exists only in the high spheres of logic and metaphysics. I grasp paradox within my own experience. As an uninhibited pragmatist and “psycho-logician” addicted to experience lived, I need to observe three more less logical but de facto things people use to do:

(d) You misunderstand, deny or refuse to consider the statement altogether;

(e) Live humbly with a few paradoxes unresolved as any true believer does;

(f) Transcend or transgress (with or against method) the frame of reference given, the one that makes the statement or the situation impossible, and even, if needed, you transgress, uncaring of the rules given for proper thinking, like a barbarian cutting the Gordian Knot in Alexander-style.

I also believe that we can do better than remain at solving, banishing, denying or misunderstanding paradoxes.

We can put them to use. As they are.

*

Paradoxes outside the field of logic and mathematics

Academic definitions appear to consider only logical and mathematical paradoxes expressed in propositions made of words, symbols or numbers. But paradoxes are, in Culture and in everyday life, more than propositions. They appear in situations, perceptions, feelings, actions, images, symbols and so on. Many domains other than logic encounter paradoxes.

General dictionaries, concerned with what the words usually refer to or in what way they are normally used, are inclined to give more practical and wider definitions to the term paradox (my highlighting):

“1.a. A statement or tenet contrary to received opinion or belief; often with the implication that it is marvellous or incredible; sometimes with unfavourable connotation, as being discordant with what is held to be established truth, and hence absurd or fantastic; sometimes with favourable connotation, as a correction of vulgar error...

2.a. A statement or proposition which on the face of it seems self-contradictory, absurd, or at variance with common sense, though, on investigation or when explained, it may prove to be well founded (or, according to some, though it is essentially true).” (after Oxford English Dictionary, 2009)

“Paradox [Gk paradoxon], contrary to expectation.

1: a tenet contrary to received opinion

2 a: a statement that is seemingly contradictory or opposed to common sense and yet is perhaps true

b: a self-contradictory statement that at first seems true

c: an argument that apparently derives self-contradictory conclusions by valid deduction from acceptable premises

3: something or someone with seemingly contradictory qualities or phases.” (Merriam-Webster, 1994)

I observe that the defining features are, in this wider sense, features that strike us when we meet paradoxes: unexpectedness, differing from common opinion on the subject matter, surprising method or conclusion, being unbelievable, amazement, absurdity, consternation, contradiction but also…the potential to express the complexity of truth (7) and wisdom, as they appear to us in "real life".

As a consequence, the public concern could be more discerning than just finding the errors and reducing paradoxes to accepted knowledge.

It may in fact be interesting, instead of finding error, to examine all shocking newness on merit. In the sixteenth century many people spoke of the Earth’s motion as the paradox of Copernicus and Galileo (8). Quite often, in common place terms, one man’s clear idea is another man’s paradox (especially when the one man’s idea is new).

A moral philosopher like S. G. Stent, finds that paradoxes are generated by our rational faculty in domains where rationality tests its limits and deep truth is sought; free will vs. determinism, soul, moral responsibility...(9) I find this idea of testing the limits intriguing and fascinating too.

It may be worth, besides the hunting for precision, which is too often a surrogate of truth (10) and for certainty, which is not of this world, to uncover, disguised in paradoxes (11), some hidden occasion to learn and to be wiser. I believe that wisdom – which is for me the person-centred, good sense, shared understanding of knowledge and experience – must often be expressed in the form of paradox. Its complexity requires the gamble of contradiction and the prudent discerning of obscure formulation.

The impression they give, of surprise and absurdity, makes paradoxes (or appearing to be paradoxical) a familiar ingredient of ridicule and of jokes – the pun that provokes laughing. In this wider cultural meaning, paradox is then a recipient or a vehicle of esprit de finesse and of humour.

If it looks like one and works like one...it is one

Let me go further and shift the discussion from paradox to paradoxical.

An openly subjective view of paradox, a working definition as my “everything experienced as a paradox” takes the discussion out of pure theory, into the practical province of thought, experience and action in everyday life.

When you come to “living persons”, anything could "be" paradoxical, that is received as a paradox, if it appears as strikingly new, contrary to established opinion or belief, self contradictory, serioussly unexpected or compelling in what it shows or implies, but is impossible to understand.

Such a light and situational view of paradox is less concerned with what paradoxes must be but rather with “how they behave” and what they do to people.

Psychologists found real life abundant of “double binds”, cognitive dissonance, moral dilemmas and so many other blocks, states or situations that look to me very much like paradoxes with or without words.

For authors like - in my youth - Paul Watzlawick, paradoxes, as bugs in the mind, are frequently the very form in which difficult problems are created and in which locked solutions induce and perpetuate a crisis they are meant to prevent or resolve. Many self perpetuating problems can be identified in such dysfunctional blind spots.

Parents, teachers, lovers and leaders give sometimes paradoxical instructions, make conflicting demands that paralyse and beat the mind when the victim is unaware and unable to discard them:

“Be spontaneous!”

“Do not read this sign!”

“Be natural!”

“Be yourself!”

“Be independent!”

“Go to your room and don’t come out until you have a smile on your face!”

“Don’t take notice of my presence!”

“You should trust me!”

“Why don’t you want to love me?”

“I want you to like me of your own free will!”

“Discipline must be freely accepted!”

“You must change the way you think!”

“You must stop believing this!”

“Don’t think evil!”

“Please ignore my previous mail”.

Orders of this kind are impossible to obey from the very moment they are uttered. They are seemingly meaningful but contradictory and absurd. Their impact is destructive or at least destabilising. They may create “double binds” as described by Gregory Bateson in the ‘1950s. Such tension unresolved is a provocation to madness or at least, to duplicity and double-talk. These “games of not playing a game” create the problem they pretend to prevent. The skill to detect such paradoxical circumstances allows one not to solve them, but to detach from their grip, cope with them or to evade them by rebellion.

The Prisoner’s Dilemma proposed by game theory generates situations of paradox – trust versus irresistible rational distrust (see William Pounstone, Prisoner's Dilemma, Oxford UP, N.Y...,1992). Common sense distrust leads the “prisoners” to act in a vicious circle, in the name of compelling prudence, finally against their best interest and to their inexorable loss. On reflection many situations where mutual exchange is based on trust turn to paradox: applying the millennia-old Golden Rule or Kant's imperative to only do what could be turned into a rule applied by all, generate situations of paradox. Likewise, the necessity to surrender some freedom to others and to submit to laws in order to stay free is, at core, paradoxical.

The study and the diagnosis of paradox proved also to be a gold mine of original, often paradoxical solutions to blocked situations and impossible problems. Psychologists found that prescribing paradox – making a situation as absurd as possible - can lead to the solution of seemingly insoluble situations.

Another field rich in paradoxes is art. Artists like Maurice Escher or Salvador Dali demonstrated to our eyes impossible perceptions “that can’t be, but still are”.

Image paradoxes typically called optical illusions are coercing the spectator (or the victim) to perceive things that can’t be, according to common sense; Impossible triangles, water flowing down - upwards, hands drawing each other. These are paradoxes formulated not in words but as objects and perceptions grew to be part of the universal visual vocabulary of humanity.

This is not only amazing and beautiful. It is challenging; I also found those images eye-opening. I used such optical and other illusions to help people learn with their own eyes that seeing is not always believing. There are few such ostensive means to persuade one to become more critical with the obvious.

Literature is another source of paradoxes (12). Writers like Franz Kafka and George Orwell exposed entire totalitarian dystopias were words mean their contrary and where people are damned if they do and also damned if they don’t. Jonathan Swift, George Bernard Shaw, H.G. Wells with his time machine, Oscar Wilde ("Those who try to lead the people can only do so by following the mob”), Lewis Carroll, Joseph Heller (Catch 22) are a few examples of literature rich in highly meaningful paradox.

Private and corporate lives are crawling with the absurdity of political correctness, double-talk, perverse effects, vicious circles and structural contradictions. Aren’t all these paradoxical? Paradoxes that appear as dissonant structures of people and contradictory, self-defeating relationships?

Situational and organisational paradoxes are less studied scientifically, at least by the end of the twentieth century (or I do not know enough about that study). An investigation of organisational paradoxes identified eleven of them: stability vs. change, empowerment vs. control, people focus vs. organisation focus, consistency vs. flexibility, internal vs. external, narrow vs. large picture, means vs. ends, soft vs. hard, individual vs. group, words vs. actions and trust vs. mistrust (13). Some of them may be structural or they stem from the self-fulfilling prophecy or compelling paradigm of a founding father. Such paradox will re-create itself for a long time before being exposed as utopia or dystopia. Others are, I think, “ways to hell paved by good intentions”, group-think and perverse effects of cultural bias and politically correct hypocrisy in big organisations.

A whole political system can become a paradoxical one in which, as my mother - a historian - used to jest, even “the past is most difficult to foresee” because it will be continually falsified to fit current dogma. Under totalitarian tyranny – right or left - contradiction is carefully cultivated between thought, speech and action. In such worlds good is bad, truth is lie, freedom is submission, ugly is beautiful, soldiers fight against war and everybody is born a sinner and a suspect, doomed to prove his innocence forever. Orwell and Kafka and Soljenitzin describe such tyrannies at their extreme.

Religions like Taoism and Zen Buddhism appear to use paradoxical Koans in order to produce major liberating change by crisis in people’s mind. The stress of trying to find the meaning of paradoxical statements, differentiating things from themselves or of achieving spontaneously prescribed states of mind destabilises, it seems, to the point of producing quantum leaps of faith or of comprehension. Many sects seem to use such devices to lure people into leaps of faith in the opposite direction of dependency.

*

While reading this enumeration, you may believe that I write here to deplore paradox for its negative instances of manipulation and suffering. However, as I announced, my goal is different. I stress how the ubiquitous paradoxes feel and “behave” because I seek to learn something useful from what they do to people.

What good things could we do with such painful paradoxes?

Let me affirm the enlarged field once more. For me, as a psychologist, if people experience something as a paradox, then, for them, it is one. The impact will be that of a paradox. I mean to say that being paradoxical will suffice for any item to institute a “paradox” locally. You can paradox most of the people some of the time… and that is enough.

Observing this feeling of paradox I appreciate the value of such things, narratives and situations that act upon people’s minds, surprise, challenge or numb them and leave them as perplexed as the electric-eel of Socrates is reputed to have done. I look at this traditionally disquieting field with the eyes of the teacher and of the giver of counsel.

The following will then be my working definition:

For this paper paradoxical is something (a statement but also a thought, a feeling, an object, an image, a question, an instruction, a choice, dilemma, a situation) that leads into or keeps our perception, our reason, our feelings or our action in an impasse and which invites surpassing, some radical change of mind.

The premises or perceptions leading to an experience of paradox are obvious, acceptable, plausible and compelling. My eyes or ears, my fingers, my experience, should not cheat me, and the reasoning or the perceived transformations appear to be sound and self-evident to my common sense and my intuition. They may even be necessary to logical thought (as logical paradoxes show to be). However, the meaning implied or the conclusion reached appear impossible and with no way out.

It had better be a joke. The feeling of paradox is most often irritating, even threatening. What befalls me goes against my common sense, against the stability and coherence of my world. It undermines my certainty, my faith. Some simple, basic, unquestionable values and deep beliefs, about truth and reason, my very intellectual makeup may be threatened if I take this seriously. If God Almighty cannot (or can) create a stone too huge for him to lift is He almighty? I feel tired to think further. I better laugh it away and say that it is stupid. Or stone the author and burn his book. Or quit. I am so busy with other business.

Living a paradox leads us through mental dissonance; it may also open us to new, reformed understanding.

In time, my own encounters with paradoxes taught me something I call fascinating: The “paradoxical” gut feeling of experiencing something “impossible” is a unique symptom. A symptom of touching one of two limits of my mind:

(1) its’ outer frontier – what I don’t know (and did not know that I don’t know), or

(2) its’ inner foundation – the obvious, the basic unquestioned “axioms” that guide my reason, my values and my daily life.

I mean that the feeling of paradox is a “detector of the Unknown” or an “exposure of unexamined certainties”. As Proclus wrote "Just as sight recognises darkness by the experience of not seeing, so imagination recognises the infinite by not understanding it..."

When I write about the outer frontier of the unknown I have in mind one of its major problems; that we usually don’t know what we really don’t know; and not only by definition. Of all people, those who need most to grow and change to the better, are unaware, even totally unaware, often in denial of their ignorance. How to find out the direction in which we need to seek? By what means to become aware (as Socrates made us) that we are ignorant where we believed we knew?

Dramatising and making intuitive about what, or in what direction we are ignorant, is in my opinion precious for both the masterly teacher and the deserving learner.

The same applies to the other end, so to say, of our usual lack of critical thinking concerning the obvious. I even believe that the unexamined obvious is a worse enemy of learning and changing than unsuspecting ignorance. Received beliefs or past successes become part of our persons and certainly of our culture. People are made of their preconceived knowledge to such an extent that they feel deeply threatened when their basic beliefs are questioned or put to test.

The paradoxical way of compelling one to reconsider the “obvious” is one of the rare means to access the strongholds of the mind.

If what I claim is true it means that we have here a tool to detect that which we do not know or cannot conceive or never considered critically. Allow me the metaphor: I call it a philosopher’s stone of critical thinking (14).

*

Let me pause and take leisure by recollecting some old examples of paradoxes:

The strongest paradox known in history is probably the one “of the liar” that of Epimenides the Cretan who claims that all Cretans are liars: a correct statement that ends up in havoc: I read:

“This statement is false.” A medieval formulation of it is this imaginary argument between Socrates and Plato:

Socrates: Everything Plato will say here is false.

Plato: Socrates spoke the very truth.

If this is true, it is false. If it is false, it is true. This is not normal. This is not what I learned in school. The disciplined mind needs to solve this. For my undisciplined mind this is a provocation to ask what truth is.

Many grains of sand form a heap. If you take away one grain, it is still a heap. You keep taking grains away. When is the heap no more a heap?

I do not care to solve the vagueness problem, but it makes me think of soft water drops that pierce hard rocks. It reminds me that it is the last straw that breaks the camel’s back. The accumulation of small nothings may bring big change.

I will ask you to answer with “yes” or “no” only, the following question: “Will your first answer to this question be “no”?”. If you say “yes”, you lie. The same if you say “no”.

If you give a thought to this impasse, it is one little example of how language is relative and limited; there must, of course, be something like language about language. There may also be times when we should free ourselves from words.

An example of paradoxical ruse:

Euathlus the apprentice lawyer had a contract with his teacher Protagoras the Sophist master; he would only pay a fee for the teaching if he won his first case in court. Euathlus had a clever idea. He sued the master himself to obtain free tuition. If he would lose this first case, he had nothing to pay, as agreed. If he would win, he will not pay, by force of law.

Just imagine the endless ruses this “turning a thing on itself” can inspire. And imagine the power of being able to change the frame, the context by which meaning is given.

The Zen teacher formulates koans, questions impossible to answer:

“What happens to my fist when I open my hand?”

“What is the sound of one hand clapping?”

“If a straight line is an infinite circle, then where is its centre?”

“Kuang Tze dreamed one night, he was a wonderful butterfly, enjoying the breeze in the sunny field. Then, he woke up and he didn’t know any more: was he Kuang Tze heaving dreamed being a butterfly, or was he a butterfly dreaming now that he is Kuang Tze?” (Chuang Tzu, The Inner Chapters)

The growth solution of a koan is (in my opinion) to gain autonomy from the question itself. It is formulated with the intention to exasperate the learner to such an extent that he would in the end break the “catch” in a sudden illumination that all the rules can be disobeyed and transgressed in the mind. This is, in intellectual terms, a satori. Perhaps...

Religious ethic has its paradoxes too:

If God is good, all-mighty, and all-knowing, then how can

there be so much suffering and evil in the world?

The result was scepticism and loss of faith for some or endless theodicy to justify God’s ways for others. For me this mainly demonstrates what happens when abstract ethic meets complexity and life. It tells me that ethic choice is our mind size struggle with disorder in the name of being as good as we can. It means that there is as much goodness in the world as we put into it.

My favourite creation of a mild feeling of paradox by utmost banality is to tease you:

“I will here and now create, because I please so, a piece of truth that I challenge you to refute if you can. Here it is: ‘There are only two kinds of people: Those who believe that there are only two kinds of people, and those who don’t‘”

Let me stress this: we can create a feeling of paradox. We can generate and wield the magic wand of paradoxical experiences, to make people’s minds open and move.

*

The question that inspired this paper is: “Why is Paradox so fascinating?” It is time to justify my answer: “Paradox is fascinating for me because it makes reason bend beyond itself. I understood as I kept teaching and growing older that, in everyday life, paradox is not only a mere “bug in the mind” but also a Master tool. I will try to explain this by example, through my own way of rediscovering the ages old tool and of using it.

Paradox is fascinating as an instance of learning from not understanding.

Carefully administered, the puzzlement induced by paradoxes enables me and the people I work with, to detect things beyond the field of what we already conceive: “Just as sight recognises darkness by the experience of not seeing, so imagination recognises the infinite by not understanding it.” (Proclus Lycius, 412-485 AD, A Commentary on the First Book of Euclid's Elements).

I realise that this is quite a strong statement, laden with metaphor. I do not intend to appear mystical. The fact is that this observation seems to work. I believe that understanding and using paradoxes allows a practical approach to our inner limitations, structural or caused by ready-judged ideas, stubborn received beliefs about undecidable issues, unshakeable values and other convictions, too deep or too obvious to be a likely subject of critical discussion. I will take an example from my experience (15) :

How I teach by confusing people

One of my favourite classroom koans in a course of wisdom (which I disguised for many years as a “Management” course) was to lure the participants into an exercise of inventing “things impossible to imagine”. It was an exercise of creativity (16) which I dubbed “a can opener for the mind”.

First I would ask several groups to compete in inventing as many possible things one can do with “bricks”.

This is a very well known and slightly worn-out classic of brainstorming and the participants used to have – as I intend – an appeasing feeling of déjà vu. Easy! Soon, most people understand the playful rule of the game - that we are free and legitimate in the mind to invent whatever we like, provided there are no constraints of rule, law or material limits. They discover that they can even redefine “bricks” to mean whatever they fancy.

After this first teaser, when people were pleased with themselves, I unexpectedly declared that “all this was no real creativity since we only imagined things possible to do with “bricks””. “What about some real creation,” I propose, “like inventing the same amount, but of things impossible to do with “bricks”?”

Now this is a paradoxical injunction and people fall into it, regularly. They are stunned.

First, my students rushed mindlessly into listing a large number of “impossible” things thus contradicting themselves; once they imagined them, how could those things be impossible to imagine? I had to point out that minutes ago they accepted that “everything” was possible in the mind and they just took advantage of this freedom rule.

Now, after some work of challenge, people grew to accept that only very, very few things can be retained as impossible in this occasion. For an example, stating that a thing is not what it is may be retained. Perhaps. This was voted by a majority’s common sense as “really impossible”. The exercise did not end with this.

Now I would ask, again surprisingly: “If it proves almost impossible to find things impossible to imagine, why did we, minutes ago, and why do we imagine so few in our daily life; not do but at least imagine? Where is lost the rest of infinity?” A very formative discussion followed, where engineers, economists, I.T. experts and profit minded managers proved passionate interest for philosophical speculation and meanings of invention.

Reads confusing? All this is very confusing for people who take part in the exercise and I had to appease their feelings, as some felt suddenly lost and inferior. The important thing is that one after the other, at different speeds, people discover by means of this confusion that they have a number of basic assumptions, so obvious to them that they never considered questioning those axioms until this moment. Some feel uneasy but all learn something important. What is it? Participants are left deeply impressed after this exercise.

The unease and the confusion of being paradoxed are privileged ways of coming close to what we do not understand, aware that the obvious can be shallow. A Buddhist saying reminds that “the foot feels the foot, when it feels the ground”.

In the best Socratic tradition, the intuition of being helplessly ignorant in a field where I had no doubt, allows me and pulls me to open and learn new things.

The exasperation of Paradox not only challenges people to grow more open but also gives them a hint where to go and how. It points at a frontier, a rationally conceivable limit of the unknown, of the impossible and of the necessary. The inevitable spirited discussion after my koan is about realms, rules and definitions, about what is possible and impossible. Existence, reality and the limits of the mind suddenly intrigue most un-philosophical people. They sense something we all learned to forget: that in the “meta” realm of the mind, protected with

armour of question marks, quotes, parenthesis and attention marks, one could transgress and reframe almost anything. One could think free. Nothing is impossible to imagination and to thought if there are no rules and no limitations. Error and disorder should not be ruled out from this creation process, as even error could be productive. Of course, error could also result from it. Later, it may be that the outcome of this imagining and trespassing into the unknown and into the impossible need be tested for feasibility to be transferred into real life.

George Bernard Shaw expresses best this enchantment of unfettered thinking in a phrase I am never tired to quote from his “Back to Methuselah”:

“People see things and ask: Why? I dream of things that never where and ask: Why not?”

The use of paradox in education, while investigating the unknown and the non understandable, grows the size of personal freedom. It multiplies choices in the mind. It emancipates people. It helps change. Fascinating, isn’t it?

*

Change is something else

Acquaintanceship with paradox helps here too, by developing the states of mind favourable to coping and surviving unfamiliar change. Let me now look at going through change and governing change.

Things that are truly new appear paradoxical. I believe that this is because they are “out of the system” of our current understanding. In fact, change itself, when it is not of our mind size, is often paradoxical to our perception: if change is too small or too huge, too fast or too slow, too unimportant or too important, too far away or too close to us – we cannot perceive it or cannot respond to it. To navigate change and to create newness

one must be at ease with the unfamiliar and the contradictory instead of becoming defensive or hysterical.

People whose occupation is to bring newness and help change to happen must learn to live with the unknown, the uncontrolled and even with the irrational, untamed for a while (17). They must be able to function even in a state of perplexity. To cope with the never-ending surprise of our fast changing world, familiarity with paradox is a necessary companion. Someone mentally accustomed to live in cohabitation with vagueness, com¬plexity, ambiguity, contradiction suspended, able to survive not understanding, is better prepared to produce something else and to cope with newness.

Learning to live with some things unknown instead of compulsively trying to reduce them to something already controlled is a key to governing change.

I derive from this friendly, non defensive attitude to the unknown, a practice of strategy of surprise in the terms of James Carse who suggests “preparing for surprise”, to complete our customary “preparing against surprise” (18). Preparing for surprise means to become accustomed with the idea that surprises – surges of the unknown - are inevitable; there are ways to respond to them rationally and optimally to overcome the biological enmity to surprise hard-wired in our species.

*

Instead of a conclusion

So, I found paradox fascinating because it is useful as it achieves a rare thing – sensing that which we don’t know.

What to do then, after sensing the unknown? That may be the subject of another essay. One, to examine the means of trespassing into the not yet known. The metaphor of the trespassing is simple: once we detected the unknown territories which we don’t even understand we could at least draw white maps of those unknown continents. Then, we could plan our expeditions to conquer the white map: Normal, study expeditions interrogating other peoples’ knowledge and understanding or bold personal inventions. Maybe even inventions that would make new knowledge arise from nothing. We could create those unknown territories. Isn’t everything possible where are no rules and limitations?

The metaphor is simple. The application may be more complicated...

An old parable illustrates the choice we face once we experienced paradox and find ourselves in presence of the unknown:

When you have little knowledge, it is comparable with the small light of a candle. Its warm flickering creates a small space of friendly, familiar safety.

If your knowledge grows, it is like a street-light. Now you see many more things and you can walk firmly. However, the dark space of night at the confines of luminosity grows too. More things unfamiliar are inevitably glimpsed.

And what happens when you become really learned? Now the space of light is great. But beyond what you know, becomes apparent and even certain huge darkness, the endlessness of things you will never know. You are left alone, small and proportionally insignificant among stars, lost in infinity.

The question is: “What do you chose? Despair in front of the unknown? Rebellion? Urge to deny or to reduce infinity to what you know? Seeking enlightenment from a prophet? Hiding humbly inside a large community of anonymous scientists and begging the future by faith in progress? Or do you accept with modest friendliness to do what you reasonably can and use wisely what you know and knowing more, while coexisting peacefully with the unknown?

*

Let me indulge, after concluding, another touch of self-critical vagueness. My own paper reminds me a story (And I hope that it leaves you with more questions than you had before reading it):

In days of old, in ancient Japan, the summer evenings, bamboo-and-paper lanterns were used, with candles inside. Someone offered such a lantern to a blind man who wanted to go home after a visit.

“I don’t need a lantern. Light or darkness is all the same to me”.

“It is not for you my friend. Without one, someone else may run into you on the road.”

The blind man started off with the lantern and before he had walked very far a passer-by run squarely into him.

“Why don’t you look out where you walk? Can’t you see my lantern?” said the blind man.

“How could I? Your candle has burned out while you walked, my poor man,” answered the stranger.

_________

* Raymond Smullyan, Professor of Mathematical Logic and part-time magician, writes of an incident he experienced when six years old. It was so intriguing that the child would remember it for all of his life: