Man teaches his measure to the Universe*

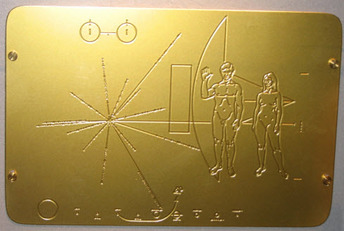

Man teaches his measure to the Universe* On this plate sent by NASA on a Pioneer mission to civilizations whom it may concern, the receiver, can see (if it is endowed with optic recognition) the proportion of two beings.

For our human eyes those shapes are two white people, man and woman, naked (probably because they are inspired by Leonardo da Vinci's Vitruvian man), but decent.

One, rises a quinary limb in what looks to me, here on Earth, as a Red Indian salute of peace, a “Stop here!” warning, or a traditionally moutza Greek insult. The human shape is proportioned to all the rest; or is all the rest - atom to Universe - related to it? Are we asizing the Universe?

Which makes me reflect to the maxim by Protagoras of Abdera, the disparaged philosopher:

"Man is the measure of all things: of things which are, how they are, and of things which are not, how they are not" [1] he said, which piqued Plato to ridicule him, because Plato believed that eternal ideas, not Man, are the reliable reference [2].

*

This saying is for me a metaphor, of us being the unavoidable container, means and valuer of knowing; for knowing is by and for knowers and nothing else. We understand the World in the manner we perceive it and interact with it, by our own proportion. We question it from our point of view, ultimately in nothing else than our human representations, metaphors and words.

Why be so defensive against this maxim? You do not want people to believe a metaphor, it is meant to be understood not believed. It is the spoon, not the soup. It is the finger that points, not the moon. Metaphors do not explain, they help to make sense in our mind. They offer a vivid representation for our conscious sense to grasp, to move, to give shape and familiar concreteness, to let our imagination compare. This is how we can handle words and meaning. In this case, we are the spoon, we are the finger, while the Universe is imperturbably as it is. Philosophers pleased however to see the phenomenology of the "man-measure statement" as the universal root of moral relativism or of unscientific ignorance; I believe that Protagoras simply refers to a legitimate point of view, which does not deny universal reality but cares for what it means to us...

“Man is the measure of all things...” indicates that, for us, in our life-space which is definitely a reality for us, things count to us as much as they relate to us, in interaction with us; they represent to us, compellingly, what they are at human scale and what they make to us and we can make to them, not in general, nor in themselves.

The thing in itself is indifferent to the person as infinity is not our house. If the human looks at infinity from his own point of view he sees immensity, something inconceivable; infinity does not see anything looking at the human, because it does not look - man is an insignificant speck of dust in the blind eye of the Universe; if human looks at himself from the eyeless point of view of infinity, he sees nothing of human interest.

*

When what you seek is wisdom rather than scientific knowledge, the giant steps of research, discovery and technology are still small steps for each single Man; the intelligent individual’s legitimate question is what use, what meaning that progress adds to our life, what worth it has for each of us. I oppose this wise questioning to the objective-minded fascination with "Big History" views from nowhere [2.1] which disenchant us humans and leave our lives meaningless. Our humanity-serving question is what understanding we gain to live happier and fulfilled, how not to be dissolved and reduced into a world of Machines.

For wisdom is a humble choice; of looking at us and the world - with taking some distance - and then, interpreting each encounter steadily from the point of view of what it is to us as persons, of what makes sense to us, of what value it has for life, for our life: How does it concern us, people? Is it good for me or bad for me? Do I like it? Is it beautiful, good, just, life-upholding? Does it add to my civilisation, to my spiritual life? How will this end? What can I do about it? What is it for us - to judge, to decide, to do, to beware? From where do we come, who are we, where do we go?...

Such purposeful Homo Sapiens bias makes knowledge human, ours, understood beyond parroted grand explanations. The rest, so necessary, so undeniably true, so powerful - facts, data, experiments, detached explanation of things “in themselves” grand laws, algorithms, theories, perfect skeletons of dried-out thought - is ascetic science and disinterested reason trying not to be human, craving to free itself from being human; that is, truth for a world without us. The Enlightenment grew that Promethean knowledge to free and to serve us but strangely it tends to free itself from us. That knowledge for the sake of itself, independent of us, its capital discoveries and its planet-changing technological conquests, require therefore constant vigilance and harnessing to join back our best interest.

*

Let us be clear, humane wisdom is not opposed to science; it is its necessary complement (even as science does not know yet how to define wisdom and how to enrich it). It would be of course absurd to say that wisdom is better than science. The vocation of wisdom is not to diminish our trustful respect for scientific progress, our learning from sensible knowledge; it is rather to grant that Science still serves us, instead of us worshipping science and - even worse - its technology.

We humans aim to know things as they are and also to judge what they mean to us, not to the infinite Universe, nor for the sake of Ultimate Truth: we need to grasp what the known is worth to us, how it links back to our needs and values and action. This entails exerting the humble but ultimate human interest of living a good, flourishing life.

Wherever science prevailed, wisdom ads worth to it as much as it interprets science in human terms, accountable to society.

Information, data, knowledge grow into understanding, servants to the conscious human person, the one who feels, says “I” knowingly, judges and chooses. By the means of science - our tool and servant - the world as it is becomes for us a charted ocean in which we can navigate aware of what we do and where we go. I would add that, in spite of universal change being ruled by necessary causes, we can still change the course of change - in what concerns us.

Where the angels of science still fear to thread, repelled by imprecision, flow, subjectivity and lack of "proper logic" (which enumeration describes fairly the real human world), wise judgement navigates alone its esprit de finesse, subtle, intuitive, too-complex-to -describe, risky, but life-saving. The wise examine good-sense consequences of what we understood, know, intend, meet and do - for the earthly life of persons. They care a lot for what we do not know or do not understand and count with such weaknesses when deliberating. Charting the unknown and living with ignorance is part of knowing. They seek the ways to navigate that great ocean or if you prefer, to explore the maze of the given, to chose, steer course and improve and complete an earthly reality we live, instead of just bearing it.

*

Above all a wise one works to turn the world mind size, simple enough to understand and friendly enough for us to act ; fools make it too complicated to cope with; or too abstract, metallic and alien, too non-human for us to survive.

Be on your guard though to the power and dangers of presenting things wisely by making them too simple with our metaphors. “Science without conscience"[3] is a cold beast; but let us add with prudence: wisdom unverified is of a blind seer.

© Ioan Tenner 2011-2019

-------------------------------

[1] in Sextus Empiricus (Adversus Mathematicos, 7.60) (Diels Kranz 80 b1):

“Of all things the measure is man, of the things that are, that [or "how"] they are, and of things that are not, that [or "how"] they are not.”

Alternative quotes:

Sextus Empiricus, Outlines of Pyrrhonism, 1.216; Diogenes Laertius 9.51.

About what the mysterious phrase may initially mean, it is useful to read Ugo Zilioli, Protagoras and the Challenge of Relativism: Plato’s Subtlest Enemy, Ashgate, Burlington, 2007

Hannah Arendt goes even deeper in restoring what Protagoras actually said:

""man is the measure of all use things (chremata) [my underlining], of the existence of those that are, and of the non-existence of those that are not." in:

Arendt, Hannah, The Human Condition, 2nd ed The Univ. of Chicago Press, 1998, p 157

Reading her interpretation I realise that the "being the measure" of Protagoras was about all things made (and maybe looked at) for the use of Homo Faber, in the life-space created by humans. It is common sense that what is made by humans and also what is made for humans to understand shall be of human proportions. This reminds me the ingenious idea of Giambattista Vico that we humans can only know the human made world, including our knowledge, the other, "natural" one being only understandable by God - said he - the one who created it.

[2] Plato turned Protagoras into a straw-man for his extravagant contrary belief that absolute and eternal ideas (finally, God) are the measure (the norm) of all things; later philosophers thought that nay, Reason, not God is the measure and judge; nowadays, triumphant Science knows for certain that Matter is the substance to be measured, the Universe – in which we are nothing – the measurer, and quantity - dimensions, weight, duration, numbers is the only measure which proves being to be real.

[2.1] A must read about the point of view from nowhere remains Nagel, Thomas - The View From Nowhere, Oxford University Press, USA (1986), which goes deep into the analysis of the absurd but inevitable tension between taking objective distance to see things from outside - from nowhere, independent of us, the knowers - and subjectively - from inside, at the same time, as we, living conscious beings, are the only possible knowers that be.

[3] Rabelais: "..science sans conscience n'est que ruine de l'âme... Œuvres de François Rabelais, Tome troisième, Pantagruel, Librairie Ancienne Edouard Champion, Paris, 1922, ch III, p.109

_________________________________

PS: This outline was reviewed in 2012 and 2013, based on my discussions with Daniel Tenner.

RSS Feed

RSS Feed