The wisdom of Montaigne is of a sort that will come to be needed again*; that of the thinker who makes his life worth living in times of the beast.

Let us face it, there is a time for everything; under tyranny, wisdom is opportunistic; or silent. Genius, to change the world, must stay alive.

Servitude is distasteful and its compromises are ugly ; you survive crawling like a worm.

But there is still choice; as the witty epigram put it in my youth,

"the race of worms is not just wriggling ilk;

some make us sick

but some, make silk" [1]

Prudent Montaigne was of the silk-giving kind. In fact he was born in silk, lived in silk and his ways were silky, pleasant to the touch. As for his work, it was of the world changing class.

Montaigne is heavy artillery disguised as fireworks.

*

Montaigne’s work, The Essays, sprouted – as a strange, untimely flower – from the middle of arbitrary rule and fanaticism, at the peak time of witch-hunting in Europe - the sixteenth century. You would not imagine living there. His feat was to plant a seed of independent thinking in the belly of the beast, without becoming a martyr. Born an insider to the system, he enjoyed privilege and approval, made a career, while being as I see him, a most effective dissident. Internal exile seems to be the way of life of genius in bad times; lack of wisdom would be to die for proud impatience of speech.

In a "disturbed sick state" of religious persecution, censorship, savage civil war and plague, in an epoch where (as it often happens in history) might was right, under the inquisitive eye of absolute Monarchy and Church, Montaigne is inner freedom, critical spirit, the I, smiling, in gentlemanly attire; a quiet one-man revolution in human dignity and civilisation. He accomplishes to live unbent in a crooked world.

Montaigne had to learn how to navigate an ocean of insecurity, a reign of cynicism, chaos, stupidity and malice; he did. His, was what I like to call a strategy of the cork - living the now, and consciously evolving relative to ebb and flow of stormy tide, with one clear, floating landmark - keep at the surface, do not founder into wickedness. His way of being free - and of freeing other people - was to craft choices to navigate the complexity of unfreedom.

*

In his daily life, he was a reliable conservative gentleman, careful to heed Christ and give Caesar what is Caesars' and to God what is God's [2]. What was his, he kept for himself.

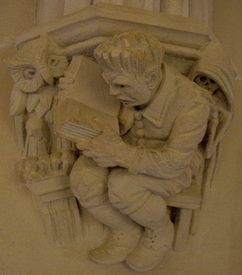

In writing, the moralist played the tradition of the wise fool, gently; behind the Fool, hides the mountain. He worked to change the world from a position of weakness.

*

While practising subversion of authority (knowingly or instinctively, what do I know?), Michel Eyquem, freshly accepted country gentleman descending from fish and wine merchants and Marrano patricians, parvenu to French nobility, achieves to be regarded and even better, to live like a grand seigneur of agreeable company and vital counsel to royals as different as Henry III, Catherine de Medici and Henry IV of Navarre.

Mysteriously, the distracted, lazy, dreamy Sieur de Montaigne, always about to retire in the arrière boutique of his ivory tower, tormented by his kidney stones, uninterested in having any power in his hands, is found discretely central in the negotiations to convince Henry of Navarre that Paris is well worth a Mass [3]. Unimportant and anonymous as he pretended to be, he still gets imprisoned at the Bastille, from where Catherine de Medici, that proverbially nice, charitable lady, extracts him urgently: "Touche-pas à mon pote!" This outsider was just too useful, irreplaceable to waste.

The apparent chatterbox was a prudent master of silence; not many people are able to speak so candidly and write so much without ever bragging or allowing secrets to escape their lips. Nothing transpires on his pages from the intrigues of the princes, the negotiations of the factions or the Bordeaux city real politics.

Because he was discreet and kept away from the civil war mêlée, he was solicited, named and summoned in absence to be mayor of the troubled city of Bordeaux, rara avis able to mediate between Catholics and Protestants under the climate well symbolized by the Saint Bartholomew Night massacre. Public savagery preserves a touch of common sense asking help from is opposite.

*

Meanwhile, he wrote and re-wrote his increasingly bold book – the lasting achievement.

He finds a flabbergasting stratagem to spread different ideas – reflexive writing. He writes to himself, about himself, as if. He does not write like others do about truth of the world, the Universe, nor about religion, just about himself, “domestic and private” ideally naked like a cannibal; it is not about reality he writes, no, no, simply about his intimate person, his body – thumb and prick included and his mind, about the strange, unimportant, private thoughts visiting his playful imagination.

He, a humble sinner, is simply spending rich hours trying his hand and fantasy at attempting mere Essays.

The Essays omit to mention how prudent and skilful he was in difficult circumstances with kings, queens and inquisitors. Instead, he only describes his skill with robbers. It was not a biography or a chronicle. For a change, he relates in detail how weak he was, the blunders he did, how he never knew what he forgot, how little he knew and how uncertainly.

In fact, he was an adroit social man, a born diplomat able to work with all warring factions at the same time, able to dialogue with Inquisition and get approved a free-thinking book by the Pope; but he does not highlight his successes or the events he influenced. He complains in detail about his pains and his clumsiness, his inattention. The man he depicts - am ivory tower gentleman so small and weak - suggests that a great spirit is amazingly simple, a human being as we all can be. This is why so many people recognise themselves in his book.

*

Montaigne is a great author, indirectly. We cannot measure his influence so much by thankful quotes from later peers as by the reaction of great authors who opposed his ideas and who built on that opposition, often without quoting his name. Influence does not mean enslaving followers, rather making people think - their way - to what you propose. He is great by "the share which his mind had in influencing other minds" [4]. Contemporaries liked his prose and maybe, the noble ladies opened their minds without detecting all the implications. Later generations lived by his ideas, often without minding the source.

His tour de force in proliferating the ferment of critical spirit was executed with such a light touch, with velvet gloves, in such a pleasant, moderate, deferential, conservative, opportunistic, entertaining, exotic, metaphoric, unassuming manner, that King and Pope actually like it; it took almost a century for Inquisition to notice the chain-reaction of critical thought set alight in 1580 by his charming gossip and to forbid the Essays in 1676.

Too late! The Montaigne attitude trickled into Shakespeare, his “I am my book” and "what do I know?" irritated Francis Bacon to retort “Of myself I say nothing” [5] and to demonstrate with Method how certainly science can know the world. His surprisingly constructive scepticism fascinated Pascal [4.a] and challenged Descartes to affirm the absolute power of Reason. He will inspire Diderot and water Rousseau. Kant knew by heart entire passages from him, and built on his scepticism. Nietzsche delighted in his critical spirit and started playing with matches. His seemingly introspective book instituted quietly the reference Weltanschauung of being civilised, of the modern individual, of equality and tolerance. If you seek an example to personify Civilization when marching ahead, Montaigne is one.

*

Why do I believe that Montaigne was wise?

Because his work appears to be the first self conscious and comprehensive attempt to query the entire European heritage "What can you tell me about how to live?" [5a]

Consider that wisdom was understood by the sages as the vehicle to living a happy life, with the meaning that such good life is one worth living. With Montaigne I find an instance to observe that the way towards such flourishing must must learn from the past, learn from Plutarch and Seneca, but also judge with our own head and fit the real world where we are born.

We may know much wisdom, generate many words of wisdom but we are wise as much as we live wisely, in such a way that makes our life enviable and admirable, in our own world, not in the next.

*

A wise life à la Montaigne, in times where persecution is at work, is one in which you keep safe, productive and free inside, while you adapt, for fear and for duty, to the sorry country and times where you are born: “I shelter where the storm drives me.” [6]

His, as Stefan Zweig observed [7] was "freedom with a rattle of chains."

This sort of Good life is prudent well being and self-respect, as much as times allow. You keep positive. You live a normal life. You enjoy each stolen epicurean moment, as the bird in hand is worth two in the bush; you keep adroitly out of harm's way, avoid hurt and poverty. Stoic sages help you at this time with a rule to consider only that which is of you, which you can do and to keep at distance from that which is beyond your powers:

“Some things are under our control, while others are not under our control.

Under our control are conception, choice, desire, aversion, and, in a word,

everything that is our own doing ; not under our control are our body, our

property, reputation, office, and, in a word, everything that is not our own doing.” [8]

For that which you agree, you do your best in full view, with modest enthusiasm; even as you can do so little. For lack of anything better, you pride questionably in the thing well done.

Where you differ, you act obliquely, by not doing the wrong thing right, by the power of inaction, absence and silence, by that which you do not do and do not say, by esoteric allusion.

You trust, perilously without reserve, a few good friends. Inside your inner garden you hide Paradise: beauty and wisdom and sincerity, in the company of the great authors who keep alight the flame of civilisation in spite of history perennially wretched.

While you compromise in all this dubious business of survival and comfort, for the sake of privilege empowering your action, you work nevertheless to be a good person, to keep hands clean, to preserve respect for yourself and the other, to give something, so that you are more than a worm.

The common intellectual will do so much and hope the better for their children. Geniuses, like Rabelais, Maimonides, Erasmus, Shakespeare, Bacon or Montaigne will also nurture a much greater plan, a Masterpiece to endure; that is paid with even murkier dissimulation, compromise and double-talk.

Of course there are alternatives to such dissembling; innumerable sincere martyrs chose to die for ideas, of few of them we even know, like Simon Peter, Imam Husayn, Wycliffe, Thomas More, Jan Huss, Giordano Bruno or Jane d’Arc. Meanwhile, the mass, chooses to drift. The worst, grow genuinely corrupt, to serve the evil masters better than requested.

*

Micheau Eyquem is the case for spoiling your kids, provided you give them the education of a prince.

His father was an energetic, rich, ambitious upstart, keen of humanistic ideals. The great books of the classics adorned his walls and his friends illustrated the best of Renaissance humanism. He imagined with them a home-curriculum in new education for the benefit of his son.

While he, the Father, worked hard and humble to grow richer and to rise to nobility, he fancied little Micheau, first surviving child, to be special, an experiment in humanism; first two years sent away in a peasant family to understand simplicity and "real life"; next several years with a Latin tutor, spoken to exclusively in Latin, to become a native speaker of classic culture and to have education tailored to him, not him cut to the size of school; after that only, he learned French as a foreign language; then he was sent to an elite college, away from home, to taste social life and constraint as it is... but still among an elite. As his father revered the sages of antiquity and collected their books, Micheau took to actually reading them, in original and without the intimidated feeling of visiting alien countries, it was his mother tongue; when home, the boy was spoilt, woken up with classic music played at his bedside every morning, never doing or learning other than what pleased him, so that he developed the taste to doing just that, all his life.

Freedom in the mind, culture, autonomy, playfulness, liking your life, indulging in vanity but not taking it or oneself too seriously, ability to think by keeping a distance, is the recipe of a critical spirit that will hover above his times.

With such upbringing, Montaigne became inclined to understand the human comedy with detachment, as if from the stars, to form his own opinion unprejudiced by what was said in the foreign language of the locals. At the same time he saw and felt things from close, feet on the ground, as simple and serious as they are for a peasant. Luckily, he was born with a pleasant friendly temper bent to avoid conflict and hurt. So he took life easy and acted always with a light hand.

Because he was allowed to feel sorry for himself, he felt sorry for other people too, animals included; he could identify with them, imagine being in their place.

Because he enjoyed life, he grew to respect life and to love it.

As he saw people around him so different, he learned to accept irreducible difference to be normal and diversity as a natural thing. Additionally, with a catholic father, a mother of Jewish descent and several protestant relatives and friends, he found religious divides irrelevant.

Then came the books, full with the sleeping wisdom of the past; he was one of those thinkers keen to learn from History; he read the old historians’ meaningful accounts and found in them advice for his own time; he saw that human nature keeps us repeating the same errors; he absorbed the many antique anecdotes and sayings of the sages and theories of the philosophers from olden times without taking them as granted; he saw that everybody had to be contradicted and no idea was too foolish to have some philosopher embracing it.

Here is one man who took Socrates by the letter. Didn’t Socrates say that the unexamined life is not worth living? So he proceeded to do examine his own life and make it worth living. He did that for decades, ceaselessly and in writing so that his book is indeed his person and matures with his mind.

Did the frontispiece of the Delphi temple enjoin the visitor to know himself? Montaigne went on to do just that, day and night, dressed or naked.

Did Socrates claim that his knowledge of his own ignorance was the force that made him wiser than all around him? Montaigne went further, to draw implications. He read the Pyrronian sceptics and was fascinated by the amplified consequence of the Socratic claim: " we know that we know nothing" into the extreme that absolutely everything is so doubtful that there is nothing we can know with certainty; this includes the good sense implication that humans – theologians and priests included - know nothing about God’s ways and thus have no reason to burn people for vain interpretations of creed. So, he turned the nihilistic paradox of absolute scepticism into a tool of freedom: I will doubt everything received, and even my own doubt, and therefore stop troubling myself with theories, keep practical and think with my own mind, as well as I can, humbly enough to avoid stupid, sufficient opinion but also boldly enough to speak with no concern of authority and dogma. I will do what my good sense suggests me and my feeble judgment confirms.

As I read my own private Montaigne – everybody does - I was tempted to interpret his life and "method" in terms of Taoist wisdom. He did not know the Lao-tzu but lived by it;

He does not push, he pulls.

Because he does nothing, much gets done.

Because he leaves space, things happen as he wants.

Because he takes sides with no one, all sides need him.

He has many friends because he is a friend.

He can do things because he keeps things simple.

He goes a long way because he goes with the water.

By knowing himself, he understands other people.

Being unprejudiced, he can talk with all.

As he enjoys himself, he has compassion.

Because he keeps steadily with the golden mean of moderation, when he is critical, people listen.

He survives for the reason that he is flexible, not the kind to die for ideas.

Because he lets live he is left to live.

Because he keeps an open house with no walls, little is stolen from him, even harm passes over him.

He is good but he carries a sword.

To be wise – he decided - is not to toil by some perfect saintly model, but to live as you are, better, as well as you can. Wisdom is permanent improvement, not distant ideal.

The unique ability Montaigne has - as a true critical spirit - is to not only see what is wrong in the evil present but also what is good in it; to see through indignant enthusiasm and to equally perceive what is evil in alternative extremes proposed, in the dogmas touted by the opponent to present wrongs. He does think with his own head, moderate and humane amidst madness . «...keep your head when all about you/ Are losing theirs’..." He would have certainly made his Kipling’s words.

Other great thinkers advise us how to become perfect. Montaigne teaches us how to live wisely and better, as we are and where we are.

© 2013 Ioan Tenner & Daniel Tenner

_______________

* It may look strange for me to write so bluntly about such a subject, in a normal time and a free country; but this is why I can do it, I am not a persecuted dissident but a retired elder man with no career ambition and no tenure to defend. Some scholars could write about this much better but they will not do it; they are wise. As for me, I believe that sharing such knowledge may be generous and useful.

[1] George Ranetti : Cugetare

“Sunt şi-ntre viermi, în viaţă

Deosebiri de clase:

Sunt viermi ce fac...doar greaţă

Şi viermi ce fac mătase!”

[2] Luke 20:25: "He said to them, "Then give to Caesar what is Caesar's, and to God what is God's."

[3] Paris is well worth a Mass (Paris vaut bien une messe) Alistair Horne, Seven Ages of Paris, Random House, 2004

[4] Hovey, K. A., "Mountaigny Saith Prettily": Bacon's French and the Essay, PMLA, Vol. 106, No. 1 (Jan., 1991), p.72 the share which his mind had in influencing other minds"

[4a] "Ce n'est pas dans Montaigne, mais dans moi, que je trouve ce que j'y vois ." Pensées (1670)

[5] “De nobis ipsis silemus” Francis Bacon, The Great Instauration, preface to New Organon

[5a] Schneewind.,J., B., Moral Philosophy from Montaigne to Kant, Cambridge U.P., Cambridge, 2003

[6] Horace, Epistles I.i.14)

[7] Zweig Stefan, Montaigne, PUF, Quadrige, Paris, 1982

[8] THE ENCHEIRIDION OF EPICTETUS in Epictetus, Vol II, Harward Univ. Press, Loeb C. L., Cambridge, 1952 p 483

I thank Professor Claude Blum and Classiques Garnier Numérique for precious access to the magnificent Corpus Montaigne, Classiques Garnier Numérique http://www.classiques-garnier.com/numerique-bases/index.php?module=App&action=FrameMain&colname=ColMontaigne

RSS Feed

RSS Feed