One of my competitive advantages in life was learning early that you do not need to know everything, it is sufficient to know where to find it [1]. I opted for the nimbleness of a "A well made rather than a well filled head" as Montaigne wrote [2] while other people confused themselves by gobbling everything presented to them.

However, now I must reconsider and ask again: Is that so? Is that sufficient?

The world changed. Finding becomes easy but flooded by overload. Look at this pad in front of me! It contains many thousands of the best humanities in the world: writers of the great literature, sages, thinkers, legends, myth, fable, proverbs and sayings, sacred writ of great religions, history, philosophy, sculptures, paintings,... and also the best dictionaries, sources of quotes...* The sleeping wisdom of the World...

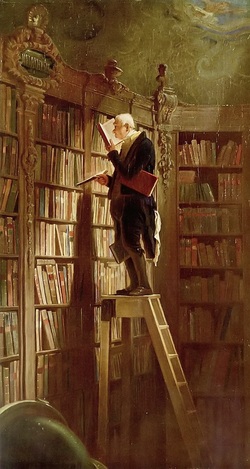

I made my book-hungry father's dream come true and honoured his memory with a library larger than whatever he ever hoped. Only kings and Universities were able to have such libraries in the past. Here and now, the tomes are (almost as if) all laying in my lap. I posses the books, I have them, well, I have copies of copies of copies of them. Now what, Ioan?

Truth hits me right in the face, all this wisdom is still asleep for me; I cannot own these books, they are not mine; when I touch them with my eyes they turn into deep forests, impenetrable tomes to explore, erudition branching our into the infinite. I can embrace my laptop but not the knowledge of humanity. The books would be mine only after I took time to absorb the marrow of the whole lot in my mind and also adopt their ways of thinking in the working of my mind. A child can count on his fingers that in the best of cases I cannot hope enough days left in my life to read all this, and even less to assimilate it and make it mine.

*

In fact, even if the brigand rapacity of the copy right businesses, the impudent paywalls and the censorship of the tyrants or the snooping mania of terrorized governments do not choke the open access to culture on Internet, we still head into a Huxley-world of cheap zillion channel Television and mystified Internet and "mobile", so called networked civilization, where people become unable to read books, in spite of all being available to them. As Neil Postman [3] wrote, George Orwell described a "1984" world where people were forbidden to read books, while Huxley drew one - much worse - in which people will be incapable to read.

As I see, this world is coming alive now.

Even without gate-keeping and censorship, another evil monster advances, the deluge of undiscerning quantity and purposeful confusion or fake, which conceals the valuable culture in an ocean of rubbish. If you do not understand in advance what you seek, and how to recognise it when you find it, you are lost. Unprotected with a life buoy of general culture and critical spirit, you will drown. As if a subtle devilish adversary were working against humane civilisation, against our passion to know and understand, with a perverse strategy applying in reverse the old wisdom: "If you want to grow it, water it. If you want to kill it, flood it!" We are flooded.

For the young Internautes of humanity, this implies, now, a choice between a new kind of education equal to the best of the elite education of the past and yet another middle age century of numerate illiteracy and ignorance. This time it will be darkness in full light, immune to learning, because of believing to know enough!

*

How to prepare for the flood? What to do under the deluge of confusion?

Obviously we must learn to float and navigate across a global ocean of debris and disinformation. We must consider what deserves to be taken aboard to be saved from the soiled ocean of globalised "knowledge".

*

To help myself across immensity, I devised my personal strategy: to go back to square one – in haste – and like legendary Noah - who saved exemplars of the essential species - to select and take aboard only the time-tested great books of humanity most needed to reproduce Culture, wisdom, and to save that humane erudition which I call humane Civilisation. Read them first, I told myself, at the source, ad fons, all the rest can wait; This seems to work. Unfortunately. it only works for me in private, such passéisme generalised would unjustly kill almost everything recent. How sinister it would be to drag humanity back into the past, how unfair to the bright new creators! They do bring new value into this world, and they keep civilisation alive.

I gained temporary advantage though; from the time I started my cultural fundamentalism strategy, I felt less confused and I learned much quicker, with less spam in my eyes and ears. I feel relatively secure because I see the way and I have a key, a compass to guide me. A few great books are now mine too.

Gradually, by the wealth of reading, we become a little more aware from where we come and what our words mean. Definitely, I know today much more about the immensity I do not know and even comfortable with it. In this, I am that much wiser.

Mine, is a strong survival strategy, for a while. (But understand me well - this is only a temporary strategy of urgency, not a long term solution.)

*

Seneca the philosopher was more radical, as he limited the choice to conformity:

"...reading of many authors and books of every sort may tend to make you discursive and unsteady. You must linger among a limited number of masterthinkers, and digest their works, if you would derive ideas which shall win firm hold in your mind. Everywhere means nowhere. When a person spends all his time in foreign travel, he ends by having many acquaintances, but no friends...

... So you should always read standard authors; and when you crave a change, fall back upon those whom you read before. Each day acquire something that will fortify you against poverty, against death, indeed against other misfortunes as well; and after you have run over many thoughts, select one to be thoroughly digested that day. This is my own custom; from the many things which I have read, I claim some one part for myself..." [4]

*

Michel de Montaigne has another approach, careful to avoid choking his own spontaneous thought from the interference of other peoples' books:

When I write, I dispense of the company end memory of books, less they interrupt my own wording. I skim through the books, I do not study them; what stays with me, I do not reckon anymore as being somebody else's." [4a]

Later, another great thinker, Arthur Schopenhauer, proposes another reason to only read selectively, by thinking first your own thoughts and reading afterwards to complete them:

"...much reading deprives the mind of all elasticity; it is like keeping a spring continually under pressure. The safest way of having no thoughts of one's own is to take up a book every moment one has nothing else to do. It is this practice which explains why erudition makes most men more stupid and silly than they are by nature, and prevents their writings obtaining any measure of success...

Reading is nothing more than a substitute for thought of one's own. It means putting the mind into leading-strings. The multitude of books serves only to show how many false paths there are, and how widely astray a man may wander if he follows any of them. But he who is guided by his genius, he who thinks for himself, who thinks spontaneously and exactly, possesses the only compass by which he can steer aright. A man should read only when his own thoughts stagnate at their source, which will happen often enough even with the best of minds. " [5]

*

If selective reading is not sufficient remedy, what else?

The bad solution to the immensity of the past is certainly the current, dominant one: specialise yourself into a corner, live in a box and ignore the rest. This arrogant choice of expert ignorance is grounded by a blurred, unexamined belief that – with the progress of science and technology – the old writings, the past, grew obsolete and only recent things count because they carry the superior future. Worst than this techno-scientist cult are only the radical rejections of culture: “We don’t need no education...” or the one-book-culture of the zealots.

On this mind-narrowing path of tight separation by disciplines we also lost the way of reasoning of the universal genius... We wait, I believe, for new giants of synthetic mind like Aristotle or Leonardo, Montaigne, Shakespeare or Newton, or Einstein, not blinded by technology, method and gain, to turn their genius towards the human condition and culture today.

*

There are some other solutions to immensity, trusting witness and common sense:

We have a possibility to trust - for a while - some recent well read sages to select for us credible lists of books worth reading; they cannot be however technicians alien to the cultural heritage which “does not compute” and certainly they cannot be little-red-book activists or firm monist believers of whatever exclusive creed.

If you make this choice, there is good company available to join. Great writers use to share what they read and advise what is worth. Some lettered trials are the life-time reading plans of the Western Cannon and the Eastern one:

Harold Bloom proposed the Western literary Canon [6] Read the books he listed and you will be a cultivated Occidental... and a few years older. For a shorter kind of list, Italo Calvino would probably inspire you [7]

{UPDATE august 2018 } In 2018 as I revisit, all the web adresses are now obsolete- fatigue, life, small egos incapable to give away, indolence, copyright trolls devoured them. At this time try other excellent links tested until October 2019 (or learn to do web research):

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Western_canon

http://www.openculture.com/2014/01/harold-bloom-creates-a-massive-

http://www.interleaves.org/~rteeter/greatbks.html

An Eastern canon must be added to the Western, to speak meaningfully about a world culture: a trial among several is at Online Literature.

Indeed, how could you write about culture, without minimum minimorum reading sacred writs of the East, like the Koran, Tao te Ching, Confucius, Buddha, Zoroaster, some Upanishads, some Egyptian and Tibetan books of the dead, to complete our Hebrew and Greek roots? How to ignore Gilgamesh, the Persian poets, The Chinese Arts of War, Zen haikus and the oceans of streams of "Indian" stories from which come most of our tales, fables and dreams?

If you chose this path of following mentors - and you should do it with patience - with some perseverance and while still young enough, you will find plenty of good leads and pleasure, rewarding juicy fruit. You will find even here on Earth, another, richer, world of spiritual elevation a citadel of freedom in the mind to complete you view of the World and to protect you in this obtuse material world of the daily life. An inner paradise in which your mind has more words understood and thus more choice and freedom to think with your head and act as a person.

*

To travel in the empire of books, we require an education of search for our own voyage.

We need to learn how to learn. That means going beyond learning what we are taught or whatever is cast under our noses.

Beyond just being instructed with what is given to us and beyond striving vainly to know everything, we need - to have a chance of freedom - to learn how to discern and chose, how to weigh critically, how to judge, how to discard and how to forget. We need to learn how to keep aware of what we do not know and find out and remember where to find the things we do not hold in mind - when we need them.

This learning means that you proceed to build your own head, a habit to ask questions and to evaluate what you found, to ask:

“Really?"

"Who says so? Based on what?” to say

“I like this, but not this.” and

“Sorry, this I do not understand.” and

"Interesting! Important! I keep in mind where to find this and who can help me to understand it when needed."

Such style of learning is built traditionally on being educated by example, in an educated family or by great mentors. For the art of reading books, you need masters, not instructors, certainly not instructions. "programmes" and "trainers".. The internet explorer deserves an aristocratic education, not a democratic one, else his intellect will become run-of-the-mill trash carried by digital tides.

To stay clean of litter coming our way, we also need a re-education of the quote-culture; most of the rubbish that pollutes the mind on Internet today drips from imbecile attribution of ideas and phrases to people who never said them. By some candid perversion, it became usual to "quote" boldly, without indicating who and where and when.

To really understand an idea you must know its parents.

Keep in mind that a quote quotes!

We also need the technology, the software, to turn towards content, with tools serving the seeker and not only the offerer, the client instead of the advertiser and the seller. We need applications to haunt and crawl the net and find what we want instead of landing on what is advertised or offered within a bubble confirming what we believe already. We need reliable references of seriousness and value, by credible people.

We need urgently search engines to search for us us not only on the Net but also home, on our own hard disks, to find things in our own overgrown treasure trove: to find what we need quickly and accurately enough, in the place where we know it to be hidden.

Today, I still do not find the simple decent private search engine which - like Google - would dig out the paragraph, the phrase, the idea I need, when I need it, not on Internet but here in my lap, on my own computer. A profusion of technicians do not seem to understand or better said do not care for the usefulness of helping us, private persons to find things in our own treasury chest.

*

Well, this being the disquieting state of the matter it is still true that a voyage of a thousand miles keeps starting with the one next step; any good book is a door to everything else. In spite of my anxious look at all those tomes, it is never too late in fact to start reading a great book, any good book, as a first step.

It was well said that even a little learning, no matter how late in life, makes radical difference, as in one of my favourite parables, like a small candle lit in the dark. It kindles a warm little nest of light, much friendlier and totally other than the chilling darkness of ignorance.

------------

*and I left aside Music and Science and particularly everything else I forgot this day.

[1] “You don't need to know everything, just know where to find it.”

No, it is not from Einstein, nor an American president! Exact quote with context: “A clergyman should be well equipped for indexing the best he reads in books and for filing clippings. Educated people are not those who know everything, but rather those who know where to find, at a moment's notice, the information they desire..." The Expositor and Current Anecdotes, Volume 16, Indexing and Filing, 1914-1915, [INDEXING AND FILING, Advertisement for Wilson Index Company of Lynn, Massachusetts] Page XX, Column 2, F. M. Barton, Publishing, Cleveland, Ohio. Quotation appears two pages after page 744 on a page labeled XX) This, cf. Quote Investigator to whom I thank again for their work.

Rectification on 3 October 2012: The original source appears to be Samuel Johnson: "Knowledge is of two kinds. We know a subject ourselves, or we know where we can find information upon it. When we enquire into any subject, the first thing we have to do is to know what books have treated of it. This leads us to look at catalogues, and at the backs of books in libraries." — Samuel Johnson (Boswell's Life of Johnson, Ed, A Birrell, Westminster, Archibald Constable and Co, 1896). Thanks to John I. Spouge for looking deeper into the well of the past.

[2] Explains Montaigne: “ For a child of noble family who seeks learning not for gain (...), or so much for external advantages as for his own, and to enrich and furnish himself inwardly, since I would rather make of him an able man than a learned man, I would also urge that care be taken to choose for him a guide with a well-made rather than a well-filled head; that both these qualities should be required of him, but more particularly character and understanding than learning; and that he should go about his job in a novel way. (my bolding; IT) Michel de Montaigne, Of the education of children, in SELECTED ESSAYS TRANSLATED, AND WITH INTRODUCTION AND NOTES BY DONALD M. FRAME, Classics Club, WALTER J. BLACK, • ROSLYN, N. Y. , 1943

[3] Postman, Neil, Amusing Ourselves to Death: Public Discourse in the Age of Show Business. USA: Penguin Books, N.Y., 1985. A book to read carefully, I am afraid. The exact quote from the Introduction: “Orwell warns that we will be overcome by an externally imposed oppression. But in Huxley's vision, no Big Brother is required to deprive people of their autonomy, maturity and history. As he saw it, people will come to love their oppression, to adore the technologies that undo their capacities to think. What Orwell feared were those who would ban books. What Huxley feared was that there would be no reason to ban a book, for there would be no one who wanted to read one. Orwell feared those who would deprive us of information. Huxley feared those who would give us so much that we would be reduced to passivity and egoism. Orwell feared that the truth would be concealed from us. Huxley feared the truth would be drowned in a sea of irrelevance. Orwell feared we would become a captive culture. Huxley feared we would become a trivial culture, preoccupied with some equivalent of the feelies, the orgy porgy, and the centrifugal bumblepuppy. As Huxley remarked in Brave New World Revisited, the civil libertarians and rationalists who are ever on the alert to oppose tyranny "failed to take into account man's almost infinite appetite for distractions". In 1984, Huxley added, people are controlled by inflicting pain. In Brave New World, they are controlled by inflicting pleasure. In short, Orwell feared that what we hate will ruin us. Huxley feared that what we love will ruin us. This book is about the possibility that Huxley, not Orwell, was right.”

[4] Seneca, Epistles to Lucillius, II, Loeb, tr Gummere

[4a] My light translation of " Quand j’escris, je me passe bien de la compaignie et souvenance des livres, de peur qu’ils n’interrompent ma forme. (III 5, 874b) Je feuillette les livres, je ne les estudie pas; ce qui m’en demeure, c’est chose que je ne reconnois plus estre d’autruy (II 17, 651a). " Quoted from Michel Magnien, "Montaigne et Erasme" in p. 24 in Smith, Paul J. K. A. E. Enenkel - Montaigne and the Low Countries (1580-1700)-BRILL (2007)

The references (in parantheses) to the Essays are from Michel de Montaigne, Essais III 2 (Paris: 1588; Ex. de Bordeaux) 353r ; éd. P. Villey (Paris : 1965) 810c

[5] Schopenhauer, A., ON THINKING FOR ONESELF, in THE ESSAYS OF ARTHUR SCHOPENHAUER Tr T. BAILEY SAUNDERS, THE ART OF LITERATURE Volume Six, Penn State Electronic Classics Series

[6] Bloom Harold, The Western Canon, The Books and School of the Ages, Harcourt Brace, new York.., 1994 Harold Bloom's WESTERN CANON is outlined conveniently at THE BOOKLIST CENTER (not working in 2019)

[7] Calvino, Italo, Why Read The Classics?, Vintage Books, New York, 2001

There are many other credible sources:

The editors of The Norwegian Book Clubs asked 100 prominent authors to nominate ten books that, in their opinion, are the ten best and most central works in world literature: THE 100 BEST BOOKS IN THE HISTORY OF LITERATURE (lost in 2019)

Borges, Jorge Luis; Eliot Weinberger (ed.,tr.); Esther Allen (tr.); Suzanne Jill Levine (tr.); Selected Non-fictions Penguin, 2000

http://www.cse.iitk.ac.in/users/amit/books/borges-2000-selected-nonfictions.html

RSS Feed

RSS Feed